I bet quite a few Norton and Vincent fans have glanced at the photographs accompanying this article, and felt it was a desecration to amalgamate their favourite marques, no matter how desirable the outcome. Well, in response to that, I can do no better than quote the machine’s original owner, who wrote in the early 1990s; “In these days of classic bike restoration, the very idea of a Vincent combined with anything else may well represent an anathema to purists. However, if one runs the clock back to 1960, when a different set of 'desirables' applied, then it may be admitted as understandable.”

Sadly, Pete Ross – the man who penned those words – is no longer with us, but I’m indebted to his memoirs for information about this superb and unique machine, and thanks to Kempton Park Autojumble Supremo Eric Patterson I have the considerable pleasure of riding it today.

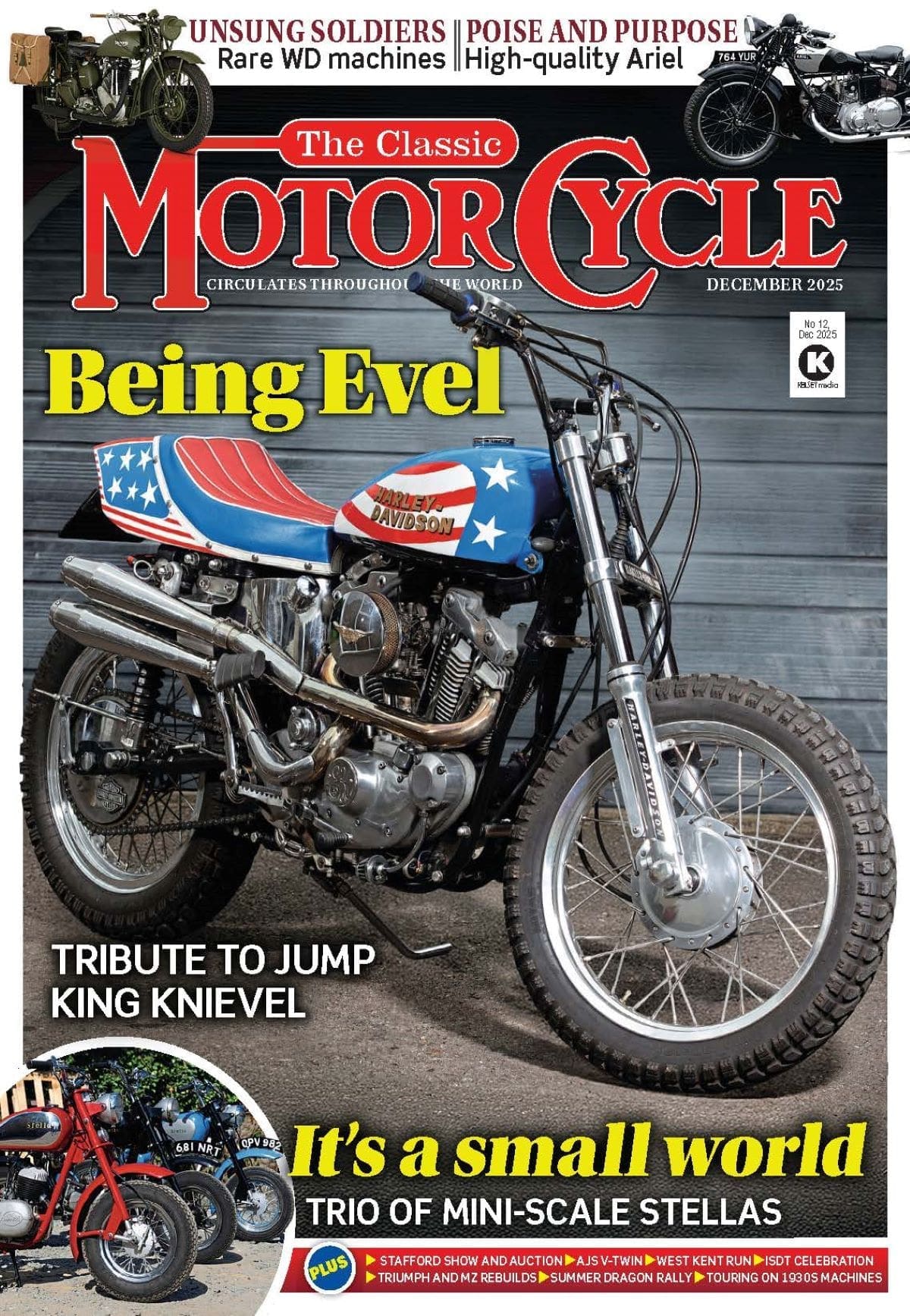

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Sadly, some specials are built simply to attract attention, but serious builders usually endeavour to create the ultimate combination of power and handling, and in the late-1950s there was absolutely no doubt where those attributes were to be found. Consequently, there was quite a vogue for putting Vincent engines into Norton Featherbed frames and the results – usually called NorVins or Vintons – predictably ranged from the really appealing to the truly appalling. One of the best, and most successful, was built and raced by Peter Darvill, who ironically became better known during the 1960s for piloting comparatively standard machines in long-distance production bike races.

Sadly, some specials are built simply to attract attention, but serious builders usually endeavour to create the ultimate combination of power and handling, and in the late-1950s there was absolutely no doubt where those attributes were to be found. Consequently, there was quite a vogue for putting Vincent engines into Norton Featherbed frames and the results – usually called NorVins or Vintons – predictably ranged from the really appealing to the truly appalling. One of the best, and most successful, was built and raced by Peter Darvill, who ironically became better known during the 1960s for piloting comparatively standard machines in long-distance production bike races.

Then Staffordshire motorcycle engineer Tom Somerton came into the picture. Buying the Darvill racer, he embarked on a campaign to commercially produce road/race Vincent/Nortons, and to emphasise that they were limited production machines rather than amateurs’ specials, he gave them the new brand name of ‘Viscount.’ It was a business venture doomed to fizzle out with a dearth of donor engines and the impossibility of producing the motorcycles at a marketable price, but it gave rise to a few remarkable machines, and the very first was bought by Home Counties’ enthusiast Pete Ross.

Pete had been a fan of Vincents since he bought a Comet while doing his National Service in the RAF. To be precise he was a fan of the speed, Vincents could provide, and although the 500cc single was one of the fastest things in its class, he soon found it was no match for the current parallel twins, so he part-exchanged it for a Triumph T110. In turn, he found that the Tiger couldn’t stay with Vincent’s bigger V-twins, and traded it in for a Series D Black Shadow.

The Black Shadow was a race-proved development of the Rapide that had appeared just after WWII, and it significantly added to performance that was already the stuff of legend. The Rapide could comfortably exceed 100mph – in an age when an 80mph Hunter or ES2 was considered quite sporty – but the Black Shadow had polished engine internals, bigger carburettors and high-lift cams, and could achieve that speed in third gear. When Motor Cycle magazine had one on test in 1949, its top speed had to be estimated at 125mph, because there was literally nowhere in this country where it could be reliably measured!

The Black Shadow was a race-proved development of the Rapide that had appeared just after WWII, and it significantly added to performance that was already the stuff of legend. The Rapide could comfortably exceed 100mph – in an age when an 80mph Hunter or ES2 was considered quite sporty – but the Black Shadow had polished engine internals, bigger carburettors and high-lift cams, and could achieve that speed in third gear. When Motor Cycle magazine had one on test in 1949, its top speed had to be estimated at 125mph, because there was literally nowhere in this country where it could be reliably measured!

Even that sort of drive didn’t satisfy Pete Ross’s lust for performance, and after tuning and streamlining his Shadow he achieved a two-up top speed of 130mph, which he dryly said; ‘wasn’t bad for 1958.’ Perhaps fortunately, his passenger’s remarks weren’t recorded!

He then read about Tom Somerton’s plans, and dashed off to see the prototype Viscount. Pete liked what he saw, and why wouldn’t he? The frame and power unit had been subtly modified to enable comparatively simple engine fitting and removal, and to improve access for maintenance. The Featherbed frame had the Manx Norton’s excellent conical magnesium hubs laced into aluminium rims, and the use of glass fibre had resulted in a weight only 24 pounds heavier than the contemporary Manx racer – a remarkable achievement for a fully equipped roadster with an engine of twice the capacity.

Pete revelled in the light handling and steering, and reckoned the weight distribution was better than on Vincent’s own design, but felt the Viscount was slower than his old Black Shadow. Somerton quickly responded by replacing the standard carburettors with TT Amals and Pete Ross duly became the owner of Viscount Number One. He was also the poorer by £450, a sum that would have almost purchased two new parallel twins, but exclusivity never does come cheap, does it?

Pete revelled in the light handling and steering, and reckoned the weight distribution was better than on Vincent’s own design, but felt the Viscount was slower than his old Black Shadow. Somerton quickly responded by replacing the standard carburettors with TT Amals and Pete Ross duly became the owner of Viscount Number One. He was also the poorer by £450, a sum that would have almost purchased two new parallel twins, but exclusivity never does come cheap, does it?

The bottom end was unchanged from Peter Darvill’s set up – indeed it apparently still hasn’t been disturbed – and Ross found the engine was ‘turbine smooth’, its silky feel doubtless enhanced by unobtrusive rubber mounting of the handlebars.

The motorcycle still wasn’t fast enough for him, though, and he soon opened up and gas-flowed the inlet ports, had the TT carburettors bored out, raised the compression to 11:1, fitted a Gold Star silencer and added a streamlined fairing.

In this mode he took the Viscount to the Isle of Man, where he lapped the TT course at 85mph on open roads, and clocked more than 140mph on the drop down to Creg-ny-ba! The performance – even though it was perfectly legal at the time – highlighted the deficiencies of contemporary tyres, and the back one unsurprisingly blew out on the M1 after 50 miles at 110mph! Pete Ross also found, even with improved ventilation, the brakes were incompatible with motorists who didn’t expect a motorcycle to be travelling at three-figure speeds, and so he decided to extend his activities to the race track.

With so much power already on tap, only fairly superficial changes – such as the fitting of a dolphin fairing, short alloy guards, a single seat and rearset controls – were required, and for a while Pete became an enthusiastic and relatively successful club racer. Marriage and work then curtailed his activities with the Viscount, but it remained in occasional use almost up until the early-1990s. By then Pete Ross’s final illness had persuaded him to put it into touring trim, with less lumpy pistons, a nose fairing, flashers, mirrors, a luggage rack and a dual-seat, but luckily the special parts such as the mudguards had been kept safe.

With so much power already on tap, only fairly superficial changes – such as the fitting of a dolphin fairing, short alloy guards, a single seat and rearset controls – were required, and for a while Pete became an enthusiastic and relatively successful club racer. Marriage and work then curtailed his activities with the Viscount, but it remained in occasional use almost up until the early-1990s. By then Pete Ross’s final illness had persuaded him to put it into touring trim, with less lumpy pistons, a nose fairing, flashers, mirrors, a luggage rack and a dual-seat, but luckily the special parts such as the mudguards had been kept safe.

Understandably, Pete Ross’s widow, Brenda, was reluctant to part with the motorcycle that had meant so much to her husband, and it was about three years ago that Eric Patterson learnt about its existence and whereabouts. He didn’t push negotiations, but kept in touch and after a year or so he became only the Viscount’s second owner, having assured Brenda he was buying the Viscount to cherish and use, not to sell on at a profit. True to his word, he has done little beyond restoring the machine to the form in which it spent its glory years. He’s rejuvenated the engine’s trademark black paintwork, re-fitted the GRP mudguards and hump-backed single seat, and that’s about it, other than a general tidying up of parts like the footrest hangers, which needed new spacers to properly clear the engine casings.

Oh, and there’s one thing he jokingly asked me not to mention, knowing full well that I’m bound to ignore his request in order to explain the blue haze you’ll doubtless detect in the riding shots. “A breather had been added to the front exhaust rocker inspection cover,” he grins, “and I thought it made the engine look a bit untidy, so I blanked it off and now the bike smokes a bit.” That’s putting it mildly… making repeated passes for the camera rapidly filled the narrow road with a cloud that would have obscured a battleship, let alone a motorcycle, and mechanical investigations plus re-instatement of the breather are on the cards.

Oh, and there’s one thing he jokingly asked me not to mention, knowing full well that I’m bound to ignore his request in order to explain the blue haze you’ll doubtless detect in the riding shots. “A breather had been added to the front exhaust rocker inspection cover,” he grins, “and I thought it made the engine look a bit untidy, so I blanked it off and now the bike smokes a bit.” That’s putting it mildly… making repeated passes for the camera rapidly filled the narrow road with a cloud that would have obscured a battleship, let alone a motorcycle, and mechanical investigations plus re-instatement of the breather are on the cards.

Incidentally, the exhaust has a very ordinary smell for a motorcycle with the Viscount’s competition history, but Eric agrees with the previous owner that the wonderful aroma of vegetable-based racing oil is no compensation for the shellacking and gumming up it causes.

So that’s a mild criticism out of the way, and I can get on with praising a motorcycle which is truly superb in almost every other respect. I can’t tell you how easily it starts, because I took over from Eric with the engine running, but he gets it going on the kick-start with no apparent trouble, and I certainly had no difficulty keeping it going, despite everything you hear about the temperament of TT carburettors.

And if I say the carburation is effective during acceleration, that’s a bit like saying that a scalded cat moves quite quickly. This is a motorcycle that just begs to be ridden, and ridden hard, but it’s one whose capabilities far outweigh my own. The standard Vincent Black Shadow could reach 96mph at the end of a standing quarter mile sprint that lasted just over 14 seconds, but the Shadow weighed about 80 pounds more than the Viscount, and had quite a few less ponies in the engine, so I’m confident this projectile would be well over the magic ton in 12 seconds or so.

There’s no way I’m going to attempt to prove it – although the irrepressible Eric Patterson is talking about taking the Viscount along on a future visit to the Bonneville Speed Week – but take my word, if anything beats this machine away from the lights it’ll be decades younger and have absconded from the race track. The Vincent gearbox provides swift, clean, changes and the clutch is well up to its task. It’s one of the later modifications made by Pete Ross who ditched Vincent’s own item in favour of a modified Norton clutch in the early days, and finally opted for one from a Suzuki GT750.

The Norton Featherbed frame handles the performance with remarkable ease, considering the Manx racers for which it was designed were sluggards in comparison. The whole plot feels light and well-balanced, and it’s no bother at all to chuck it round tight bends while showing off for the camera. At the other end of the scale, within the limitations of British country roads, the Viscount feels absolutely stable at speed in a straight line. Some fast motorcycles give the uncomfortable impression you’ll only remain in charge if you comply with their in-built characteristics, but this one flatters your abilities and you get the feeling it will stay rubber-side down with any sort of riding technique short of the downright suicidal. The high set footrests initially gave me cramp in the thighs, but the combination of sticky modern tyres and the frame’s abilities mean anything else would scrape the Tarmac in no time.

The Norton Featherbed frame handles the performance with remarkable ease, considering the Manx racers for which it was designed were sluggards in comparison. The whole plot feels light and well-balanced, and it’s no bother at all to chuck it round tight bends while showing off for the camera. At the other end of the scale, within the limitations of British country roads, the Viscount feels absolutely stable at speed in a straight line. Some fast motorcycles give the uncomfortable impression you’ll only remain in charge if you comply with their in-built characteristics, but this one flatters your abilities and you get the feeling it will stay rubber-side down with any sort of riding technique short of the downright suicidal. The high set footrests initially gave me cramp in the thighs, but the combination of sticky modern tyres and the frame’s abilities mean anything else would scrape the Tarmac in no time.

Just for the record, the Viscount is based on the Wideline frame Norton had replaced with the Slimline version by 1959, and I suspect it was used primarily because it was more easily available. Some pundits reckon it actually handles better, but if there is any difference, then it’s vastly outweighed by variations in the suspension and detailed design. In this case, I suspect the concentration of mass near the centre of gravity – with lightweight rims, hubs and mudguards at the extremities – greatly contributes to the light and well balanced feel. If you need convincing weight distribution makes a difference to handling, just go for a test ride on a modern Buell – designed on the centralised mass premise – and then compare it with the handling of a similarly engined Harley-Davidson!

It’s initially surprising that such a sporting motorcycle was given those enveloping mudguards, but Tom Somerton was presumably responding to current trends towards smoother styling – even the Triumph Bonneville sported an ordinary headlamp nacelle at the time – and they are obviously lighter than they look. The equally bulky appearance of the quickly detachable GRP petrol tank results, not from deliberate styling, but because it surrounds a totally separate oil tank sitting on the top frame rails.

It’s initially surprising that such a sporting motorcycle was given those enveloping mudguards, but Tom Somerton was presumably responding to current trends towards smoother styling – even the Triumph Bonneville sported an ordinary headlamp nacelle at the time – and they are obviously lighter than they look. The equally bulky appearance of the quickly detachable GRP petrol tank results, not from deliberate styling, but because it surrounds a totally separate oil tank sitting on the top frame rails.

But I wouldn’t dream of criticising the looks, because they are part and parcel of a motorcycle with an extraordinary amount of personal and automotive history to go with its fabulous performance. Eric Patterson recently took the Viscount back to show Brenda Ross, and I bet she was pleased as punch to see that not only does it again look much as it did when it was her late husband’s pride and joy, but it’s back in regular use and going as well as ever. ![]()