In this second extract from his forthcoming book, Mike Lewis looks at the evolution of social motorcycling in Britain and the USA.

Words: MIKE LEWIS Photography: MORTONS ARCHIVE

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

By 1925 in America, a brand new Model T Ford Roadster undercut the purchase price of a motorcycle and sidecar combination by as much as one third, making an automobile the main contender not just for all-weather personal transport, but for light commerce and family motoring as well.

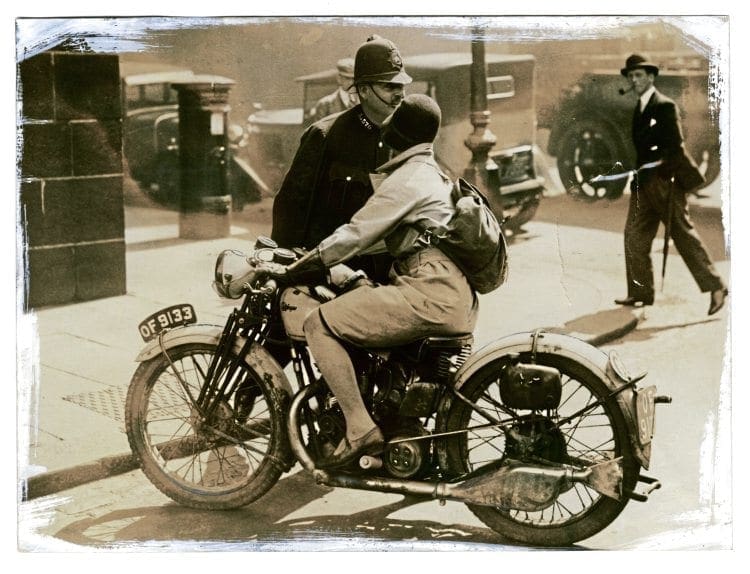

Motorcycle manufacturers now sought to expand contracts in public service applications where speed and nimbleness were paramount, such as police forces and couriers, while dealers worked hard to build customer loyalty by offering special deals and social events.

The biggest and most widespread gathering of enthusiasts was still the Gypsy Tour series, now promoted by the AMA, with aims that had been stated in the June 1922 issue of Harley-Davidson Enthusiast magazine as follows:

First-to promote good fellowship among the riders of all makes of motorcycles and to give them a pleasure tour worth talking about until the time for the next annual tour rolls around.

Second-to give the general public a convincing demonstration of the practical transportation and pleasure possibilities of the motorcycle. The more tours there are and the more riders there are in each tour, the more effective the demonstration will be.

No such organised tours took place on any comparable scale in Britain, although Roy K Battson would write in his 1974 motorcycling memoirs of this era as: “The lovely, sunlit, gone-for-ever Land which lies beyond Time’s Ridge,” when “the roads, almost literally, swarmed with motorcyclists with only the odd car or small lorry among them”.

Motorcycle clubs fostered social alliances at a time when class divisions were still rigid, also doing their bit to break down gender inequalities.

The founding of the London Ladies Motorcycle Club led to the first track race exclusively for women, held at Brooklands, and female participants soon became a familiar sight in most forms of the sport.

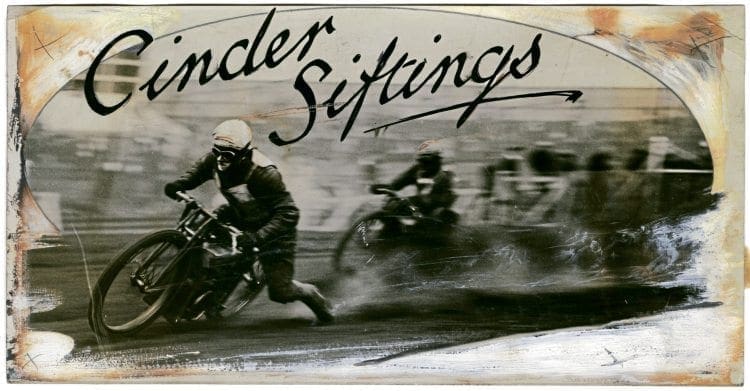

Competitive events became more popular than ever, the highly commercial new sport of speedway drawing crowds numbering tens of thousands to stadia all over the country, from 1928 onwards.

The high level of social acceptance for motorcycling in Britain partly cushioned the effects of the Great Depression, which began to gather pace in the autumn of 1929.

Hire-purchase agreements helped to keep sales ticking over, while repeal of the national 20mph speed limit at the beginning of 1931 released the motorcycle’s potential for superior performance.

This had the effect of polarising the market into stalwart utility machines on the one hand and race-bred objects of passion on the other, the 1932 Budget’s introduction of vehicle taxation rates linked to engine capacity ensuring that lightweight machines remained viable as a transport of necessity for many in the working class, who accounted for most of Britain’s 500,000 motorcyclists.

Some 25,000 women of all classes were now riders and benefited from an increasing acceptance of trouser-wearing in public, which allowed them to sit astride conventional machinery with dignity for the first time.

Royal assent was conferred by the fact that both the Duke of York (soon to become King George VI) and the Duke of Gloucester were enthusiasts, the latter sometimes seen riding his Douglas in Windsor Great Park.

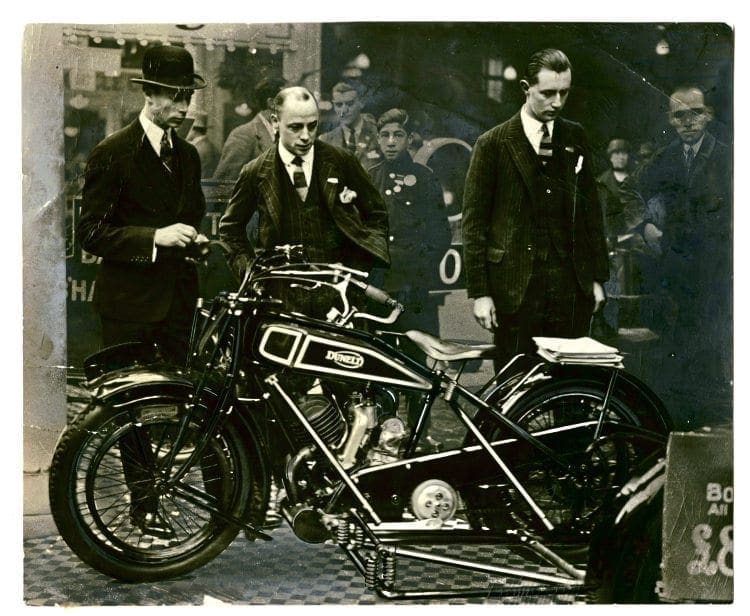

Austerity held back much technological development during the first half of the 1930s and so several manufacturers embraced colourful paint schemes to keep their designs looking fresh.

Both Harley-Davidson and Indian adopted a series of Art Deco styling flourishes from 1933 onwards, making a conscious attempt to connect with fashions in wider society, even as production levels fell to their lowest for 20 years and smaller manufacturers simply ran out of money.

American industry woes were compounded by spectator disenchantment with the racing scene, since meetings no longer showcased specially-built factory exotica as a matter of course.

This deficit was compounded by lengthy administrative debates over the merits of professional versus amateur status, so in an attempt to resolve it all the AMA introduced in 1937 a ‘Class C’ racing category for production-based machines, with the stated aims of making competition more relevant and accessible to ordinary motorcyclists.

It quickly caught the public’s imagination, encouraging a culture of amateur participation in the sport that saw hundreds of street bikes made competition-ready at weekends, with close racing virtually guaranteed.

When global conflict once more cast its shadow at the end of the decade, it introduced a new generation of young British servicemen and female WRNS personnel to serious motorcycling.

A handful of domestic manufacturers won War Department contracts for military-specification motorcycles, together gearing up to produce more machines each year than the entire industry’s prewar output.

This all boded well for a sustainable future in post-war society, given that one in five families now owned a car. Accordingly, the London Motor Cycle Clubs’ Discussion Group, representing a total of 30 organisations, appointed a special sub-committee to consider how a national union embracing all motorcyclists could be created, in anticipation of better days to come.

Across the Atlantic, a group of female riders founded the Motor Maids of America, the first article of its constitution stating that: “Membership shall consist of women who legally own and operate their own motorcycle or one belonging to a family member.”

The club received official backing from Arthur Davidson, co-founder of the world’s biggest motorcycle company, and was sanctioned by the AMA in 1941. Among those women who served as homeland motorcycle couriers following America’s entry into the Second World War was Bessie B Stringfield, who a few years earlier had become the first African-American woman to ride solo across all of the country’s 48 lower states.

The predominant American military mount was the 740cc (45 cubic inch) Harley-Davidson WLA, the equivalent of 100,000 units being manufactured (including spares stocks) up to 1945.

At the same time as millions of servicemen began returning to the United States for demobilisation, tens of thousands of these motorcycles flooded the domestic market, as they too were repatriated.

Many of the rugged V-twins were promptly repainted by their new owners and stripped of heavy mudguards, luggage racks and silencers in a process known as ‘bobbing’, the term being a nod to the cut-down ‘bob’ haircut adopted by fashionable young women during the 1920s as a sign of modernity.

Engine tuning once again became a popular pastime, particularly among fans of the newly-revived racing scene, and the result of all this work was a sub-culture based around hot-rod motorcycles that visibly stood apart from the mainstream.

The AMA’s national racing and Gypsy Tour programmes resumed in 1946, each having been suspended for the latter half of the war years, during which the US Office of Price Administration had imposed both the rationing of fuel and tyres plus a 35mph blanket speed limit.

Demobilisation largely restored the traditional demographic for motorcycling, and ex-servicemen returning to California in particular took full advantage of that state’s ideal climate and terrain to resume social motorcycling.

Physically fit and accustomed to the tight bonds of brotherhood under hostile conditions, many of these young men nurtured a distain for civilian authority and were prone to spontaneous high spirits.

They formed small clubs with mildly provocative names such as the Bombers, Jackrabbits, Rams, Satan’s Sinners, and the North Hollywood Crotch Cannibals.

It remained to be seen whether the good fellowship aims of Gypsy Tours would satisfy this new breed of rider, one whose youth had matured all too rapidly on the battlefields of Normandy, in the skies over Germany and in the North Pacific.

Next month: The ‘Hollister Riot’ (1947)

Read more News and Features at www.classicmotorcyle.co.uk and in the latest issue of The Classic Motorcycle – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.