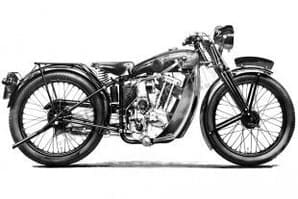

New Imperial 1901-03 and 1911-39 UK

Myths, myths and even more myths form part of the history of many marques, including one of my favoured brands, New Imperial. Thanks to Australian enthusiast Chas Lipscombe’s excellent and extensive book, New Imperial Motorcycles, the myths have been laid to rest. In promotional material the company claimed they’d started in the cycle industry in 1887. More recently motorcycle history books have claimed New Imperial motorcycle production began in 1910. Neither is correct.

New Imperial’s roots may be traceable back to 1887, but the first substantiated link dates to 1891 when the two Tonks brothers and their brother-in-law, Edward Hearl, formed the partnership Hearl and Tonks, cycle-makers. In reality the partnership, which rented premises at 84 and 85 (known as the Imperial works) Watery Lane, Birmingham, probably initially made cycle parts rather than complete cycles. By 1894 Hearl and Tonks were listed as cycle-makers and expanded their business to make the most of the boom years.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

In 1896 the Imperial Cycle Co of Manchester was declared bankrupt and Hearl and Tonks were major creditors. Norman Downs had entered the scene later to become company secretary in 1897 and then manager.

Before the turn of the century the cycle boom had collapsed. Hearl and Tonks were in financial difficulties forcing them – in modern parlance – to downsize. A combination of speculative investment, unsustainable expansion and dubious business decisions accounted for their downfall, like so many others. On 27 July 1900 the last remaining Hearl and Tonks premises at 74-76 Upper Trinity Street was handed over to the Official Receiver.

Before the turn of the century the cycle boom had collapsed. Hearl and Tonks were in financial difficulties forcing them – in modern parlance – to downsize. A combination of speculative investment, unsustainable expansion and dubious business decisions accounted for their downfall, like so many others. On 27 July 1900 the last remaining Hearl and Tonks premises at 74-76 Upper Trinity Street was handed over to the Official Receiver.

Norman Downs bought some or possibly all of the Hearl and Tonks assets. He began trading as the Imperial Cycle and Motor Co, from premises at 62 Upper Trinity Street, Birmingham by January 1901, then moved to Hack Street, Birmingham in October 1902. The first Imperial motorcycle priced at £45 was advertised in November 1901 and displayed at the Stanley Show. Claimed by some writers as the first British 500cc motorcycle, it comprised a much smaller 1½hp engine clipped to the headstock of a sturdy cycle driving the front wheel by belt. None of the pilot batch of six machines was sold; five were broken up for spares and one retained by the works as a hack.

Despite reports to the contrary and, later, Norman Downs’ claim that no more Imperials were built until 1910, there is sufficient evidence to confirm machines were made in 1902, 1903 and early 1904. How many were sold is another matter, and it’s quite possible the machines were built and listed simply to promote the company’s cycles on the theory that every good cycle-maker should list a motorcycle, too.

The Imperial Cycle and Motor Co changed its name to New Imperial in 1908, and research by Charles Lipscombe leads him to believe the next motorcycle appeared in November 1911 in readiness for the Olympia Show. It’s doubtful if many machines of the three-model range were sold, but New Imperial were back for the following season with a six-model range designed by one of their directors, Andrew Lee. Models included a 293cc JAP-engined lightweight, a number of larger singles including ohv and side-valve TT models, and a V-twin. Sidecars were on offer, too.

The Imperial Cycle and Motor Co changed its name to New Imperial in 1908, and research by Charles Lipscombe leads him to believe the next motorcycle appeared in November 1911 in readiness for the Olympia Show. It’s doubtful if many machines of the three-model range were sold, but New Imperial were back for the following season with a six-model range designed by one of their directors, Andrew Lee. Models included a 293cc JAP-engined lightweight, a number of larger singles including ohv and side-valve TT models, and a V-twin. Sidecars were on offer, too.

New Imperial continued to advance their design and model range to 1915 including offering dropped-frame ladies’ models. Then, in common with other makers, they offered an abbreviated range owing to the continuing war. Although New Imperial weren’t involved to any great extent in the supply of military motorcycles, they did develop an 8hp V-twin for the so-called Russian Contract. However, the majority of the models supplied were probably used for the Allied effort closer to home rather than by Russia. New Imperial advertising material also claimed the 293cc Light Tourist was used by the military.

Immediate post-WWI production continued with the 293cc Model 1 and 2 Light Tourist and an 8hp V-twin. A 250cc side-valve Sports Model was added in 1921 and, following Doug Prentice’s win in the 1921 Lightweight TT class, the factory offered replicas that became the Model 5 in 1922. The year’s nine-model range included the 346cc Model 6, and there was a short-stroke sports V-twin briefly listed. New Imperial continued to gain a reputation in the competition world through trials riding led by Bert Kershaw, Bert Le Vack’s second in the 1923 Lightweight TT, Kenneth Twemlow’s 1924 Junior and Edwin Twemlow’s 1924-25 Lightweight TT wins. They excelled at Brooklands, too, including wins and records for Bert Le Vack. On the back of this success New Imperial began introducing ohv sports models starting with the 344cc Model 6 and 6A in 1924.

Despite this almost roller coaster success, New Imperial then began to lose their way on the competition side, although development work on the roadster front continued, leading to the start of manufacture of their own engines for 1926, beginning with the 300cc and 344cc side-valve models and the 246cc ohv version. However, they continued to fit selected JAP engines until the 1929 season when the 678cc JAP-engined Model 8 was the only proprietary-engined model listed.

Although New Imperial were gaining TT and other race places, wins were eluding them despite the design work on the TT engine by Alf Thrush, who was then sacked after applying for a position at a rival factory. Following abortive attempts to secure the services of a few leading development engineers including Bert Le Vack, they signed 20-year-old Matt Wright. Months later Norman Downs appointed Jessie Hole (married Bill Ennis in 1939) as trials rider – a position she held until factory closure in 1938 – in an effort to attract female customers.

Keeping with fashion, New Imperial introduced saddle tanks, then lavish chrome plating and, in 1931, dry-sump lubrication for all machines except the economy 344cc Model 2. With little money and often no staff, Matt Wright got the New Imperial racing programme back on track, taking first Brooklands records, even riding himself on occasions, and then Leo Davenport’s 1932 Lightweight TT win pushing the 250cc race speed to over 70mph for the first time.

After an abortive attempt to build a unit construction under 150cc four-stroke to take advantage of the so-called Snowden (Phillip) taxation concession, New Imperial began production of the totally-redesigned ohv 146cc unit construction Model 23 (Unit Minor) in late March 1932.

After an abortive attempt to build a unit construction under 150cc four-stroke to take advantage of the so-called Snowden (Phillip) taxation concession, New Imperial began production of the totally-redesigned ohv 146cc unit construction Model 23 (Unit Minor) in late March 1932.

Despite reservations among some motorcyclists because it ran backwards through its helical gear primary drive, distrust of unit construction, doubts about its lubrication and its initially unsporting guise, the Model 23 became an instant sales success and continued to be the firm’s top seller until production ended in 1938. The diminutive Model 23 sired a whole range of up to 500cc unit models. In keeping with earlier numbered rather than named models, the unit machines gained model numbers, too. Common numbers included Model 23 = 146cc, Model 30 = 247cc, Model 40 = 344cc and Model 110 = 496cc. There were many variations, including sports versions. Despite being developed c1934, spring frames weren’t offered until February 1936, first for the 250cc and 350cc models. In addition to the unit models, New Imperial offered separate engine/gearbox models until late 1936, although the choice was gradually restricted. Race replicas were also available of the singles but not the V-twin.

Back-tracking slightly to 1934, Matt Wright at the behest of Norman Downs, developed the 500cc V-twin racer, in effect a double-up of the 250cc single. Much myth clouds these machines, some claiming they handled well, others stating they were like a camel. It’s believed the model was built in an attempt to keep Charlie Dodson on New Imps, but he later claimed not to like the V-twin. But, whatever, it won races and records, although never a TT. The factory’s last TT win came in 1936 with Bob Foster aboard a unit construction racing 250, designed a year earlier. Significantly, it was to be the last Lightweight TT win by a British factory.

Norman Downs died in 1936, losing a long battle against kidney failure. And, sadly, New Imperial were sinking financially with only modest sales, the majority of which were economy 146cc and 247cc models. On Downs’ death general manager Bill Wheeler took over as chairman and managing director.

From a situation of offering a wide model range needing an equally wide range of components, New Imperial streamlined but this didn’t work totally either. For example, sharing one frame for the 1937 250cc, 350cc and 500cc models gave the smaller model a too heavy frame which was even heavier if supplied with rear suspension.

Despite taking on aircraft work, New Imperial gave way to the inevitable in late 1938 when their bankers called in the overdraft. Many writers claim New Imperial went bust but they were never bankrupt as, after Jack Sangster bought them, all debtors were paid up in full. However, had this not happened it was probably only a matter of time before they would have become bankrupt. Limited production began again under Sangster’s control in 1939, then stopped.

Despite taking on aircraft work, New Imperial gave way to the inevitable in late 1938 when their bankers called in the overdraft. Many writers claim New Imperial went bust but they were never bankrupt as, after Jack Sangster bought them, all debtors were paid up in full. However, had this not happened it was probably only a matter of time before they would have become bankrupt. Limited production began again under Sangster’s control in 1939, then stopped.

Despite the doubtful claim by some of using the name for a projected economy model 350cc Triumph, New Imperial were finished. Motorcycle journalist Bob Currie often postulated an interesting theory which, if correct – and I believe it is – gave New Imperial life until the late 1960s. Bob claimed Edward Turner based the design of the unit construction Triumph 150cc ohv Terrier on the New Imperial Unit Minor. Turner never admitted such a thing but there are many similarities between the Terrier/Cub and New Imperial Unit Minor.

While spares can at times be difficult for many models owing to an almost unbelievably extensive range and limited production of selected models, New Imperial, ownership is great fun backed up by an enthusiastic owners association.

New Knight 1923-27 (1931) UK

Production at Bedford began with 147cc and 269cc Villiers-engined models and later included 172cc and 247cc Villiers-engined lightweights and 293cc side-valve JAP-engined motorcycles, too. Production levels were never high and doubt exists over when manufacture ended. A handful of 147cc lightweights survive.

New Map 1921-54 (1958) France

New Map 1921-54 (1958) France

Prolific, versatile Lyon factory which began production with four-stroke single and V-twin machines, including many ohv or ioe sporting models using a variety of proprietary engines including MAG, Chaise, Blackburne and JAP units. After WWII they changed focus to the lightweight economy market, building a wide range of up to 250cc two and four-stroke motorcycles with AMC, Aubier Dunne, Mondial, Sachs and Ydral engines. They also made mopeds, scooters, a 123cc micro-car and fully-enclosed motorcycles.

New Motorcycle c1925-28 France

Range of medium weight models using two and four-stroke proprietary engines built at Chatenay and designed by Georges Roy, who went to build Majestic motorcycles in Paris.

Newmount 1929-33 UK

Although flagged up in period as British-made, the Newmount began life as German Zundapp two-strokes assembled in Coventry. Assembly began with a 198cc single, then 248cc and 298cc two-stroke singles were added to the range. They later built Rudge Python-engined models.

New Scale c1906-25 UK

Last of the marques covered in this guide with ‘New’ in their brand title. A recent convert to motorcycling, Mancunian marine engineer Harry Scale rented a workshop in Vanburgh Street, Alexandra Park in 1906. Amongst his enterprises he built frames for other makers and then complete motorcycles using proprietary engines, including JAP and later Dalm two-stroke units. After WWI the firm was restructured with makers detailed as Roberts and Hibbs, Bank Street Works, Droylsden, Manchester.

Postwar launch models were powered by 348cc Precision two-stroke engines with two-speed gear and the option of clutch and kick start at extra cost. Early post WWI models were sold as the Scale but soon the name altered to New Scale. During 1920 the firm established a national dealer network, then later added Blackburne engined models including 350cc ohv and 550cc side-valve. New Scale also used Villiers and 348cc oil cooled ohv Bradshaw power. In autumn 1924, Harry Scale left his marque to establish himself as a motor engineer and months later Roberts and Hibbs sold out their New Scale business to rival Mancunian manufacturers Dot.

New Scale enjoyed only limited success in the IoM recording a fourth in the 1924 Sidecar TT and a 12th in the 1923 Senior as best results but fared much better in reliability trials, with Harry Scale winning over 100 trophies and first class awards. A small number of New Scales survive.

Nimbus 1919 -28 and 1934 – 59 Denmark

Nimbus 1919 -28 and 1934 – 59 Denmark

Despite a total production of 12,715 machines (a figure little different from Vincent) Nimbus was/is the Danes’ largest motorcycle factory. Founded in 1906 in Copenhagen by local technician Peder Anders Fisker, who then formed a partnership with Nielson. Fisker’s hobby became his career as the partnership began building and marketing electric motors. Four years later Fisker and Nielson (Nilfisk) were marketing vacuum cleaners.

During 1919 the company launched its first motorcycle, a machine of advanced, perhaps too advanced design for some, after two years experimental work led by Fisker. The unorthodox but superbly built model comprised a four cylinder in-line inlet over side exhaust valve design engine with handchange gearbox and shaft final drive mounted in a swinging arm frame.

Its tubular spine also formed the fuel tank, the rest of the frame comprised pressed steel members. Production was slow with only 10 models built during 1920. Soon the public nicknamed the Nimbus ‘Kokkenror’ – in English, Stovepipe. Never a racer, the reliable Nimbus performed well in endurance type events.

Although by nature opposed to change for change’s sake, Fisker did modify Nimbus’ only model including front fork redesign and changed the carburettor and induction manifold. After a production run of little over 1000, manufacture of the Stovepipe ended in 1928.

Hatching plans to increase manufacturing capacity to 1000 motorcycle per year, Fisker relaunched the Nimbus in 1934. Gone was the Stovepipe frame replaced with a riveted pressed steel structure, separate fuel tank and no rear suspension. The advanced in line ohc four cylinder engine pushed out a modest 22bhp at 4500rpm in standard trim, with three speed gearbox and shaft final drive.

Despite its rigid rear the MkII Nimbus gained a smart telescopic front fork predating the much copied BMW design which appeared for 1935. However, the German concept featured a type of oil damping favoured by many.

Nor was the Nimbus concept the first, although of more primitive design, makers including Scott and Rex patented and marketed their ideas of telescopic front fork before WWI. Although modified in minor detail the MkII Nimbus remained largely unaltered until production ended in 1959 leaving the factory to return to its electrical work.

Nimbus sold over 2000 examples to the military which partly explains why they maintained the supply of spare parts for many years after production ended. Although in reality Nimbus only built two distinct models, albeit in different guises, the factory did experiment with sleeve valve twin cylinder and rotary valve four cylinder design.

Despite claims of flexing crankshafts and overheating the Nimbus, ridden intelligently, proved and still does prove, a reliable long lasting motorcycle. Survival rate is good with over 50 Stovepipes and many more MkIIs in both civilian and military trim. Often machines were supplied new as sidecar outfits. Some spares are available in Denmark amongst marque enthusiasts.

Nissan 1951-56 Japan

As I don’t know of any survivors, Nissan shouldn’t be included in this guide. But… out of interest the range comprised a series of tidy models using the same 60cc ohv engine built by the renown car/commercial maker Nissan (Datsun) who began car production in 1931 in Yokohama.

NLG 1905-12 UK

NLG 1905-12 UK

Like Nissan, NLG shouldn’t be included in this guide due to lack of survivors but was briefly one of the UK’s leading sporting marques. The north London garage specialised in powerful V-twin models usually with JAP or Peugeot engines but also built a few examples with 350cc or 500cc single cylinder engines – usually JAP – including the model Victor Wilberforce entered for the 1911 Junior TT.

Although W Gordon McMinnies won the first unofficial Brooklands race against fellow Oxford student Oscar Bickford, Will Cook, riding a 984cc NLG-Peugeot won the first official Brooklands track race from a field of 21 starters over two-laps on 20 April 1908 with a race speed of 63mph. Cook added other wins to his tally with the NLG-Peugeot but fared less well with a huge 2715cc (120 x 120mm) JAP V-twin engined NLG built to challenge Henri Cissac’s flying kilometre and mile records. Although Will gained track records with the machine it never secured either British or World records despite being unofficially timed at over 90mph. Disappointed he sold it in disgust.

Other successful NLG Brooklands racers included Victor Wilberforce who later became part of the Douglas team and HE Parker. In 1909 AG Forster of NLG Motors was one of the founding committee members of the famous British Motor Cycle Racing Club – BMCRC which soon gained its renowned nickname Bemsee. Despite all its early success NLG rapidly faded from the scene.

Norman 1937-62/63 UK

Before WWI Charles Norman established the Kent Plating and Enamelling Company and was later joined in business by his brother Fred. In 1935 the brothers began manufacturing cycles at premises in Beaver Road, Ashford, Kent and during 1937 started building prototype motorcycles. At the 1938 Earls Court Motorcycle Show, London Norman unveiled their first range comprising a 125cc three-speed lightweight and a tidy 98cc single speed autocycle, the Motobyk, both with Villiers two-stroke engines.

The war over, Norman re-entered motorcycle production with a Villiers Junior De-Luxe engined autocycle and a hand gear-change 122cc Villiers engined lightweight in 1946. For the first post WWII London Motor Cycle Show held in autumn 1948 Norman unveiled an all new three model range comprising an updated autocycle – Model C – with the new upright barrel Villiers 2F unit plus the B1 (Villiers 10D – 122cc) and B2 (Villiers 6E – 197cc) motorcycles. A year later the 98cc Villiers 1F engined Norman Model D was unveiled in readiness for the 1950 season.

By adapting their standard rigid frame Norman offered swinging arm models in early 1952. Unfortunately the machine was just that, a converted rigid machine with long shock absorbers operating at awkward angles. The swinging arm models were coded B1S – 122cc and B2S – 197cc. A competition model, the rigid 197cc B2C also joined the range initially with 19in tyres at both ends but the Norman brothers soon realised the error of their ways fitting the then conventional 3.00 x 21in front and 4.00 x 19in rear tyre set-up.

Ever eager to move with the times Norman redesigned their swinging arm frame initially for the 197cc model for the 1954 season and then phased out rigid frame design on all but the competition models, autocycles and 98cc motorcycles during the year.

Charles and Fred Norman continued to modify their range to keep a firm hold on their market share leading to the 122cc Model B1S being enlarged to 147cc using a Villiers 30C engine and the introduction of their first twin, the 242cc Anzani engined TS with swinging arm frame and Armstrong bottom link front fork. Although they experimented with the larger 322cc model it never went into production but was tested by the press. For 1956 the competition model was revamped gaining swinging arm suspension, bottom link front fork and the Villiers 9E engine unit.

Again endeavouring to keep modernising their styling Norman introduced rear enclosure panels for some models and during 1957 replaced their long-lived autocycle with the Norman Nippy moped, first with a Sachs engine and later (1959) offered with the Villiers 3K unit. Towards the end of the decade Norman slowed on the model revision game but still found time to drop the Anzani unit in favour of the four-speed Villiers 2T 249cc two-stroke twin (B3 1958-60 and B4 1960-end). And during a co-operation with the German Achilles concern they offered the Lido moped and unveiled sports models of the 197cc and 249cc motorcycles.

For 1960 the 147/148cc models with either the Villiers 30C or 31C were dropped but all others continued until show time. The long standing 197cc B2SC went in favour of the updated B4C range offered in three guises, 197cc 9E for trials (which could be converted for scrambles) the B4C Trials with 246cc Villiers 32A engine or B4C Scrambles with 246cc Villiers 34A unit. Some refer to these as the B4C and B4S. While the 197cc roadster/sports B2S continued as before, the larger 249cc version were given new frames and larger tanks. The Sports model gained dropped bars, quick action tank filler and perspex screen was especially attractive while the Roadster gained heavily valanced mudguards and rear enclosure.

Age finally caught up with the Norman brothers who had been in business since before WWI. They retired, selling out to Raleigh Industries in July 1961. Soon, models were phased out and by 1963 Norman motorcycle were no more. Although never a major player in the worldwide volume motorcycle production league tables, the Norman brothers’ efforts were impressive for a firm based in Kent, rather than the Midlands, near many of the component suppliers. As well as keenly uprating their model range to secure extra sales Norman always valued trade from export, selling in many countries including Australia, coining other brand names including Rambler.

Age finally caught up with the Norman brothers who had been in business since before WWI. They retired, selling out to Raleigh Industries in July 1961. Soon, models were phased out and by 1963 Norman motorcycle were no more. Although never a major player in the worldwide volume motorcycle production league tables, the Norman brothers’ efforts were impressive for a firm based in Kent, rather than the Midlands, near many of the component suppliers. As well as keenly uprating their model range to secure extra sales Norman always valued trade from export, selling in many countries including Australia, coining other brand names including Rambler.

With an excellent post-WWII Villiers engine spares back-up and the support of the British Two-Stroke Club, Norman ownership appeals to many who value the products of a firm who often went their own way and at times bucked the trend to set their own style. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.