Quadrant 1901-28 UK

Extravagant claims of ‘Britain’s oldest motor cycle’ were made in Quadrant’s mid-Twenties catalogues. True, they were pioneers, and extremely worthy ones too, but Britain’s first motorcycle makers they weren’t. That honour goes to the Holden, or perhaps…

Not through any maliciousness, history was later created to suit the occasion and ‘known facts and history’, as I’ve discovered to my cost in the past, has been made-up for Quadrant. With this in mind, this insertion is keeping to the ‘known-and-hopefully-correct’ facts while the detail of which founding Lloyd family member did what is omitted, as the marque history is currently again under research by one of the world’s leading Quadrant authorities.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Founded c1883 by the Lloyd family to capitalise on the growing interest in cycling, Quadrant soon became a renowned maker of bicycles and tricycles. At some point a family rift developed, leading to a further business involved in the cycle trade which later also made motorcycles under a number of brands, including Dreadnought. There was also a motorcycle made under the Lloyd brand.

Quadrant, then at Sheepcote Street, Birmingham entered the motorcycle trade with the Autocyclette, in effect a Belgian made Minerva kit with 211cc automatic inlet valve four-stroke engine clipped to Quadrant cycle. Within a year, a tricycle was added, and for the 1903 season Lloyd designed a four-stroke motorcycle engine, which Quadrant manufactured. Minerva power was dropped in favour of this unit which was initially mounted within the frame diamond, but inclined forward. Later it was positioned vertically.

Quadrant, then at Sheepcote Street, Birmingham entered the motorcycle trade with the Autocyclette, in effect a Belgian made Minerva kit with 211cc automatic inlet valve four-stroke engine clipped to Quadrant cycle. Within a year, a tricycle was added, and for the 1903 season Lloyd designed a four-stroke motorcycle engine, which Quadrant manufactured. Minerva power was dropped in favour of this unit which was initially mounted within the frame diamond, but inclined forward. Later it was positioned vertically.

At about the same time, former 10th Hussars officer Tom Silver joined the Quadrant board. A larger-than-life, strong-willed character, Silver rapidly became a leading competition rider, putting Quadrant’s name firmly on the map. As well as trials and being a British team member for the 1904 International Cup Race, Tom posted the first Land’s End-John o’Groats record. Successful he was, but he also wanted to stamp his print firmly on the Quadrant marque, with later dire consequences.

Although not strictly a motorcycle, Quadrant also manufactured three-wheelers which are worth a mention as there are survivors and, of course, they’re eligible for both the Sunbeam Club’s Pioneer Run and many VMCC events, as well as VCC activities. Initially in effect a motorcycle with the front fork and wheel replaced by a forecar, then followed a banking forecar, which was replaced with a heavier three-wheeler, still of the forecar concept but with two 250cc engines.

Quadrant claimed one engine was sufficient with just the driver on board, while the second could be brought into play when a passenger was carried.

Returning to the motorcycle front, Quadrant increased engine capacity at regular intervals, with the 392cc version often raced by Tom Silver available c1904. And – bizarrely – this engine was also fitted to the three-wheeler – now called a Carette – for use when just the driver was on board, though a supplementary 250cc unit was also still fitted for additional power, if required. The motorcycle engines, still of automatic inlet valve design, were then mounted upright in the frame and capacity continued to increase.

Keeping with the times, Quadrant developed its own sprung front fork of leading link design controlled by tension springs, rather like long stand springs fitted to the counter balance of the leading link, the opposite ends tethered to the fork crown. Design was further refined and in late 1906 – in readiness for the 1907 season – a high tension magneto replaced battery and trembler coil ignition.

Outwardly, the Birmingham firm appeared to be in fine fettle, its machines were selling modestly well, trials successes kept the brand to the fore and the designs, although individual, were keeping pace with the time. But the company was about to explode.

In spring 1907 Quadrant was dissolved. Founder Lloyd moved to Monument Road, Birmingham to manufacture the new LMC, former Quadrant service manager Reg Salmson claimed to hold all Quadrant spares and was able to assist all owners while Tom Silver had moved to Moseley to build the Silver. Silver’s new machine was effectively a 3½hp Quadrant but with a conical silencer and was marketed with the slogan ‘an old friend under a new name’.

Acrimony was Quadrant’s name of the game, with Mr Lloyd stating in LMC advertising he was the inventor, patentee and designer of the original Quadrant engine. Meanwhile, Tom Silver entered the 1907 IoM TT aboard a Silver (basically a Quadrant with Silver tank badges) but retired.

How many ‘Silvers’ were made is in doubt but by summer 1907 Silver had gained serious financial backing, moved premises again, to Earlsdon, Coventry and ‘Your old friend, the 3½hp Quadrant’ was back in business, now built by the Quadrant Motor Company. By 1909 a 6hp V-twin had joined the range and the single cylinder’s magneto had moved to behind the cylinder barrel.

Sound sales of a worthy product should have led to happiness… but it didn’t! Mr Silver fell out with his new backers and revived his old slogans, this time for his new business The Quadrant Cycle Company trading from aptly named Paradise Street, Coventry. In a touch of petulance the word ‘Cycle’ was heavily underlined in all publicity material.

Sound sales of a worthy product should have led to happiness… but it didn’t! Mr Silver fell out with his new backers and revived his old slogans, this time for his new business The Quadrant Cycle Company trading from aptly named Paradise Street, Coventry. In a touch of petulance the word ‘Cycle’ was heavily underlined in all publicity material.

Soon the Quadrant Motor and Quadrant Cycle Companies merged and in 1911 motorcycle manufacture returned to Birmingham and 45-49 Lawley Street, where it remained until production ended. Steadily earning a fine reputation for well built solid big singles, the company focused much effort on the 600cc version, but V-twins were again tried with the launch of a mammoth 1129cc inlet over side exhaust valve model in late 1912 for the following season.

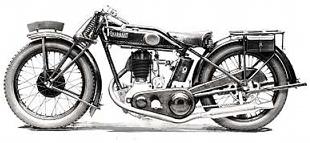

Post-WWI the company, now trading as March, Newark and Co, was never to achieve the recognition enjoyed in the pioneer days. It restarted with 654 and 780cc side-valves, followed by other capacities, then came a 292cc two-stroke lightweight. Plans for a scooter came to nothing and Quadrant weathered tighter times in the mid-1920s with 490cc side and overhead valve models and the 654cc side-valve slogger. All models were fitted with attractive mock saddle tanks; in fact like OEC they snugged between two frame top rails with a masking plate completing the illusion.

The company – who regularly proclaimed to be the UK’s oldest motorcycle marque – had one final fling in 1927 with a twin port ohv model, sporting coupled brakes but strangely a flat-tank in place of the earlier, attractive mock saddle-tank job. By 1928 Quadrant, who was strapped for cash and almost reduced to selling the fixtures and fittings to keep afloat for a few more months, completed the last few models for cash only sales.

Along with the purchase of a Quadrant comes a slice of fascinating period history, whi ch reflects the life and times of so many companies from around the globe. A history filled with ambitions, dreams, sporting success, growth, decline and some huge egos. Survival of this marque – for which I have a soft spot since a 1908 model conveyed me efficiently to Brighton on my first Pioneer Run – is good.

ch reflects the life and times of so many companies from around the globe. A history filled with ambitions, dreams, sporting success, growth, decline and some huge egos. Survival of this marque – for which I have a soft spot since a 1908 model conveyed me efficiently to Brighton on my first Pioneer Run – is good.

Quasar 1976-83 UK

Regardless of your views of the Quasar there is no doubting it was well made, fast, economical, reliable and durable. Essentially designed by Ken Leaman and Malcolm Newell with input from selected local friends the concept was sound, if you like feet forward motorcycling that is. It was powered by a 848cc ohv four cylinder Reliant engine, driving through a Reliant four-speed gearbox with Quasar conversion to positive stop change, shaft and bevel gears to back the wheel, housed in a Reynolds 531 aeronautically designed space frame, which progressively collapsed under front impact, all clad in aerodynamic bodywork.

Initial prototype work and limited early production was at Wilson and Sons workshops. Seven were built by 1980 before production transferred to Romarsh Special Products. After another 10 machines were built the company went into receivership in 1982. Three more were later built from spares.

In marketing terms, the Quasar was a resounding failure, probably because the motorcycle market wasn’t ready for such a vehicle. But also they were too expensive, too heavy and the project lacked sound marketing. As a concept for some it was a success. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.