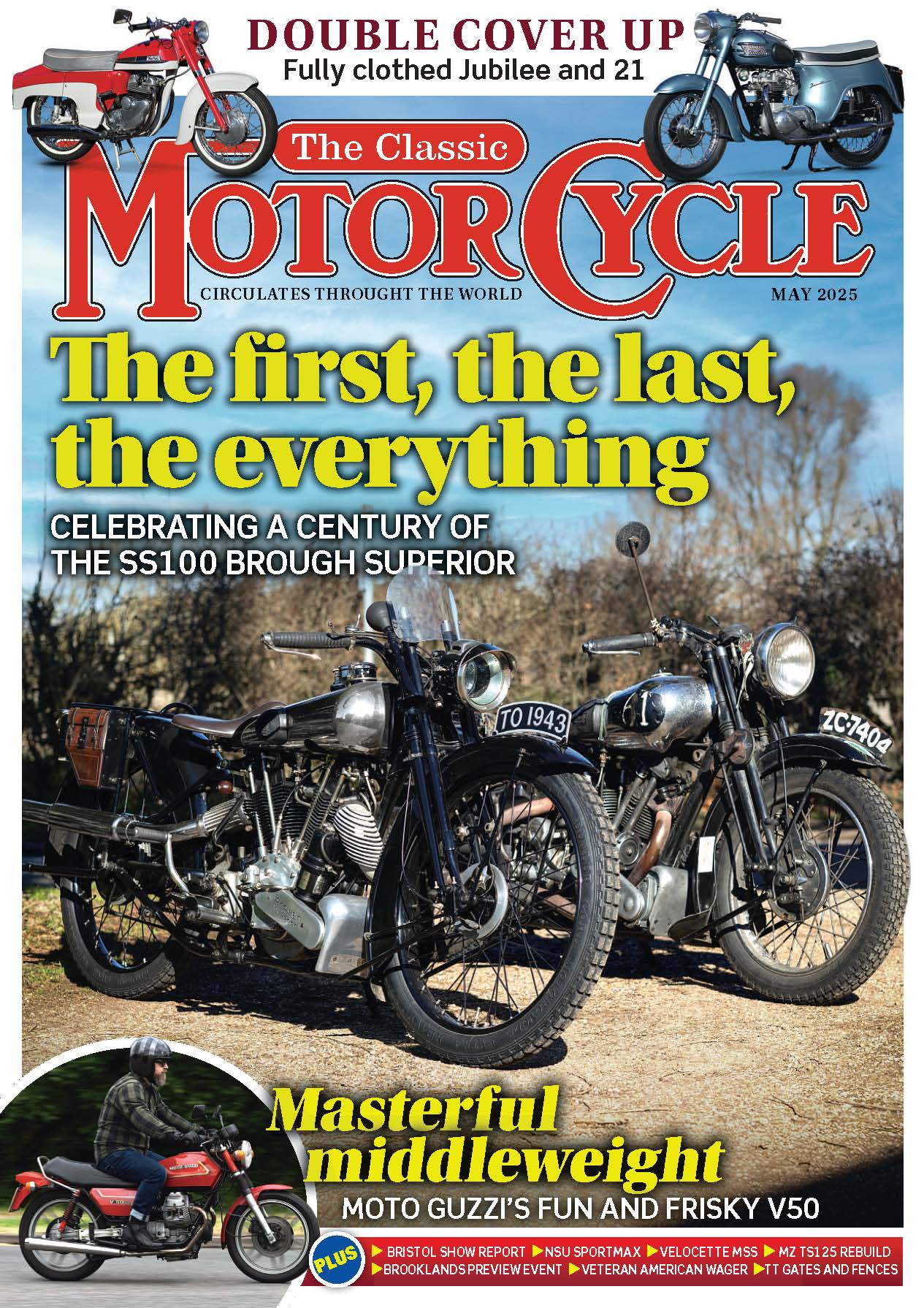

In the late 1950s, it became ‘on trend’ to offer motorcycles with enclosure, particularly of the real wheel.

Words: James Robinson Photographs: Gary Chapman

When I see a ‘bathtub’ motorcycle – generally a Triumph as they’re by far the most common – the thing I ask myself, every time, is ‘why?’ I’m not debating whether the style looks good or not (actually, I happen to quite like it as it’s of its period), anything like that, but I just have never been able to quite understand it.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The thinking, one assumes, was to keep road muck away from the rider but, really, how much detritus gets flung towards the rider from the rear wheel? None, I’d say.

Was it purely an aesthetic thing in that case? People like to say it was to do with making the motorcycle look more modern, more scooter-ish, whatever. But if so, why wasn’t the engine covered up? Surely that was the most mechanical bit of the whole job? At least when, for example, Vincent went all-in with its ill-fated Black Prince and Black Knight efforts, the engine was hidden from view too. Likewise, the Velocette LE has its mechanical bits out of the way (and was even water-cooled, to boot) as does the Ariel Leader, and even further back so did the Ascot-Pullin, for example, but the Triumphs and Nortons have their engines still on display. So what is actually the point of the rear wheel enclosure?

Spats on cars had their day in the early post second world war period, and it can’t be denied that an XK120 Jag equipped thus is possessed of a certain type of elegance different to the cars supplied sans enclosure, but one doesn’t get the sense that was what Edward Turner and co were all looking for, regarding their desire to cover up half the rear wheel. Simply, it doesn’t really make sense.

Turner’s aim

Although others had done it before as mentioned earlier (while there were more too, New Hudson comes to mind, as well as the Neracar), it was still the preserve of niche manufacturers but, from Triumph’s announcement in 1956, not any more. One of the big boys in the manufacturing playground, headed up by the biggest boy (Turner) in the design/trendsetting/self-publicity/ego world of motorcycling personalities, had decided that this was the future.

It must have been a bit of a shock but, looking at what the mercurial Edward Turner had done before, perhaps people shouldn’t have been surprised.

He had, in many ways, emasculated, or softened, the motorcycle-making scene again and again. Turner was one of the lead exponents of coming away from the ‘any colour you want, as long as it’s black’ principles of the 1920s and early 1930s, first with his red-and-chrome Ariels. While in the engines he favoured there was definitely a move away from the ‘he-man’ machinery of the period too; as a 500cc motorcycle in 1930, could there be any more difference between the overhead camshaft offerings from Norton (brute strength, single cylinder, oily, vibratory, hard, tough, manly… even called, in the Walter Moore-design days, the ‘cricket bat engine’, a proper chap’s moniker, for heaven’s sake) and Turner’s first Ariel Square Four? That was publicised by having it started by a load of schoolboys, to illustrate the ease at which it kicked up. It was the polar opposite to the big, heavy flywheel Nortons et al, where an over-advanced ignition setting would provide a belt back that’d perhaps snap a 12-year-old’s leg in two.

Easy starting and fancy colours were Turner’s first two moves away from the previously masculine world of motorcycling, and after a few years of machinations, he came out with his masterpiece, the twin-cylinder Speed Twin of 1937.

Not only was this a 500cc ‘multi,’ in a market which was the preserve of big singles, it was also painted something called ‘amaranth red’. And not just a couple of panels on the petrol tank, oh no, this was all in, with everything in dark red. A dark red named after a flower, too. And the thing was, it immediately found approval – its cheery appearance in a darkening political world greeted with wholehearted approval and praise. Looking back, it’s perhaps hard to appreciate the shift and departure the Speed Twin provided – and the fact it succeeded. It all added to Turner’s aura of being possessed with the Midas touch. All he gilded turned to gold.

And so that was that, as Turner tweaked and developed his range, adding sportier versions (the Tiger 100) and then a larger incarnation, the Thunderbird. It was always reckoned Turner was loath to increase the basic 500cc engine capacity, but he was shrewd enough to see that what America wanted, America had to have. And even if he didn’t really want to make the T-bird, he still gave it a finish, style and name, plus the performance which meant America went crazy for it. Then came the Trophy models, as well as the Tiger 110.

But one feels these were getting further and further away from what Edward Turner really wanted a motorcycle to be and, thus witness his almost antithesis to the models (T-birds, Ton tens, Trophies) that had made Triumph into what it had become – by introducing the Triumph 21. There’s surely something to be said about the power of the man, that he was able to convince anyone he had to convince (if there was anyone he had to convince) that the way he wanted to take the Triumph range was the opposite, frankly, to what looked to be most obvious.

Turner got his way. Writing in their book Triumph 350/500 Unit Construction Twins Bible, authors Peter Henshaw and Justin Harvey-James state: “The Triumph T21 was designed from the outset to attract new buyers looking for neat, inexpensive transport.” Not your McQueens, Brandos, Ekins and Eastwoods then.

Turner had form for this – see, for example, the Second World War period 3TU – and his aims were laudable of course, but those wanting ‘neat, inexpensive transport’ had turned to other offerings; scooters and microcars chief among them and, soon, small cars – the Mini of 1959 chief among them. And to think, the T21 was launched just two years before the Mini. That was what the people wanted of their neat, inexpensive transport ultimately and no amount of ‘scooterising’ a motorcycle was going to change that.

But the fact it was styled thus perhaps also took away from the fact that the T21 was actually the first all-new Triumph twin since before the Second World War, while it was the first twin to be unit construction too, and it truly was unit construction with the right-hand crankcase casting also housing the gearbox cluster, albeit with a separate oil supply, as did the primary drive. Henshaw and Harvey-Jones comment: “True unit construction engines share their drive between engine, gearbox and primary drive.” But in all other manners it was unit construction, which was a real step forward in ‘tidying up’ and modernising the engine. Perhaps it was for this reason that Turner opted for leaving it exposed?

After the 350cc T21 was launched in 1957, the 500cc 5TA Speed Twin followed in 1959 (with the T21 also renamed the 3TA); writing in The Triumph Speed Twin and Thunderbird Bible, Harry Woolridge says: “The new, unit construction Speed Twin was identical to the already established 350cc model Twenty-One. Typically Triumph, it had all the attributes one had come to expect from the manufacturer. It combined the weight of a light-ish 350 with true 500 performance.

“Its style may have been rather unorthodox, when compared with previous Speed Twins, but with its sleek lines and partial enclosure, it could be thoroughly cleaned in 10-15 minutes, a point appreciated by the majority of its riders.”

Perhaps that is something underappreciated – how it was easy to clean, rather than how it kept its rider clean though, really, has anyone ever bought a motorcycle because of how easy it is to clean? – although the front mudguard soon gained recognition as the most efficient out there too.

Still, this all felt a bit out of place, as American influence was becoming ever stronger, the teenager was only a few years away and, well, in a world of miniskirts and pointy Chelsea boots, the efficiency of a mudguard was about as exciting as lukewarm Bovril; the kids were less and less interested in doing the sensible thing like their parents wanted, with excitement and hedonism, if not the norm, then the dream. But that was all still in the future.

And so, against this backdrop, to the Norton.

It was no coincidence that I used a Norton as an example of a leg-breaking big single earlier; Nortons were and are the most manly of machines. As a pal of mine once said: “A Norton isn’t using a sledgehammer to crack a nut, it’s using a sledgehammer to hit around the roughly right area until the nut has had enough and cracks.”

But this featured Dommie, rather than an all-new model, is simply an update of what had gone before, which was an update of what had gone before that, which was based upon Bert Hopwood’s 1948 Model 7. There was to prove to be plenty of life in the old dog yet, as the same engine basically was stretched further for more models (650s as Manxman, 650SS, Mercury, the 750cc Atlas and Commando, then finally 828cc Commando) while the frame made it to 1970 too.

For reasons which now seem dubious if not wholly flawed, Norton – or more precisely, its owner, Associated Motor Cycles which, it should be noted, never decided its Matchless and AJS products needed the rear enclosures – went along the route of rear enclosure. As with the Triumph, the Dominator De Luxe (as it was to be called) called upon a smaller model in the maker’s range, in this case the 250cc Jubilee, introduced in 1957, for its inspiration. But rather than being like the Triumph an enlargement of an all-new smaller version, the Dommie De Luxes were a strange amalgamation of the race-bred Featherbed chassis – famously associated with Geoff Duke and his ilk and then still the choice of privateers in top level motorcycle racing – but with rear enclosures seemingly borrowed from the Jubilee, itself finding its influence in scooters.

So the story goes, to enable the fitting of the rear side panels, seemingly styled by someone who’d had a good look at the Nash Metropolitan too, the rear subframe of the famed Featherbed frame had to be altered. Previously, the subframe and the front frame loop were of the same width but, now, the rear was slimmed down and the straight tube up from the swinging arm pivot area to the rear of the seat was replaced by one with a curve in it. Why this was done (the curve) is unclear, but the new frame soon earned itself the moniker ‘Slimline,’ with the old, original Featherbed retrospectively becoming the ‘Wideline’. This all came about in 1960 and straight away Norton didn’t force the enclosure on its customers, insomuch as there was also available an unfaired version of the new Slimline, while the panels weren’t fitted to the 350cc single cylinder Model 50 and 500cc ES2 either. This was more than Triumph did, as the Twenty-One and 5TA Speed Twin buyer wasn’t given any option at all for the first few years.

My intention was that this feature compare and contrast the two models, with the Triumph basically an overgrown 350, now of 500cc, while for some reason I had it in my head that this Dominator was an 88, so of 500cc, too. Now, I really don’t know where I’d got that from (although the 1961 Norton catalogue does say the 88 is in red and dove grey, the 99 blue and dove grey, perhaps that’s the answer?) though it was advertised in dealer Andy Tiernan’s advert for £5000 (and had sold by the time we went to see it, to New Zealand, in fact) so whether I just muddled it up and read what I thought was there, I’m not sure. Also, just after we went to see Andy, he brought in a Tiger 100A, finished in an attractive two-tone paint finish, which would have photographed even more spectacularly alongside the red-and-cream (sorry, ‘dove grey’) Norton too. But, sometimes and annoyingly, that’s just the way it goes.

What was supposed to be a ‘how do a big little ‘un and a small big ‘un compare?’ pretty much went out the window – apart from the fact the Dominators, in 500cc and 600cc forms, were exactly the same physical size and so they could be compared from that point of view. Simply put, the Triumph feels so much smaller, toy-like even, and that’s despite the Slimline Dommie frame. I suppose the wheel size has a lot to do with it, the Triumph running on 17in front and rear, as opposed to the Norton’s 19in both ends, while it’s also interesting to compare the weights as well – 350lb against 400lb. For the record, the Triumph seat height is given as 28½in, wheelbase 52in, the Dominator’s 31in and 55½in respectively. Those statistics just underline that there is quite a discrepancy – the Norton is a bigger motorcycle all round, despite the Slimline tag.

As the visit to Andy Tiernan’s came the week after the Irish National Rally that my cousin Peter had travelled over from Australia to attend, he decided to come along with me. In the late 1950s, Peter’s dad, my late uncle Mick, had a Twenty-One, which he bought new. Peter (owner of a fine collection of classics in ‘Oz’ himself; his KTT was in our March 2019 issue) was keen to come and have a look at the Triumph, mainly as he’d never ridden a parallel twin, despite his having owned all manner of classics over the years. And there’d be the Norton to sample too.

What did we find? Well, both started easily enough, the benefit of being twins. And they did exactly as we expected – the Triumph is joyous and playful, its small, cheeky size meaning it’s like riding something of smaller capacity. The Norton, meanwhile, is a bigger lump, heftier and more serious.

If I was going for a long ride, it’d be the Norton every time, but for doing as we were now – passes for the camera, turning in the road, paddling backwards etc – everything in that manner, was just easier and more amusing on the Triumph. Accelerating away and buzzing about is where it excels – the Norton is less frantic and more grown up. Chatting to my dad that evening, he remembered going on the pillion of uncle’s Mick’s Twenty-One when he was about 16 (his brother two years older) all the way from Norfolk to Stroud in Gloucestershire with the local Triumph OC. If I was doing that journey, I reckon I’d prefer the Norton… but then I’m not a teenager. Dad does remember riding his brother’s old Triumph though: “It used to weave alarmingly, though it never seemed to worry Mick…” The Twenty-One didn’t last long before Mick bought a Velocette Venom, which started a long-time affinity and influence for the marque which ran through my dad, brother, cousin and of course me. But that’s a different story.

To the here and now. Which one makes the better buy? Well, arguably the only true ‘bathtub’ is the Triumph, while the Meriden machine’s smaller dimensions all round give it an appeal too. The Norton, however, feels like an actual adult’s motorcycle – that bit more serious-and-steady. There’s no danger of it weaving at speed, I’d surmise. As far as I’m concerned, in an ideal world I’d have one of each, of which I’m sort of halfway there with the two-tone, but I’d still not bet against a bathtub Triumph appearing in my shed before long…

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.