Although originally of German conception ‘DKW RT 125’ this pre-war advanced design impressed the British who took it as war reparations – since then the Bantam has become quintessentially British. After the austere war years a simple and economical commuting motorcycle was ideal and became very popular. Two-stroke engines were not a speciality of BSA, which surprised the market by introducing this new model in March 1948.

As its name implies, the Bantam is a small and lightweight runabout which enjoyed popularity during the 1950s and 60s as it was affordable at £60, reliable and easy to maintain.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

This fact was noticed by the General Post Office, which ideally employed many for telegram delivery, they became a familiar sight on our roads and were painted ‘Post office red’. Even in Kenya, where the authors spent their childhood, Bantams were present in respectable numbers functioning well in the hot dusty climate and unsympathetic road conditions.

The manufacturer who made the Bantam, BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) was originally a gun factory in Birmingham that opened in 1861 and became a massive enterprise. Of course, this company does not exist anymore, unlike its main rival/stablemate Triumph, which still continues the British tradition, making excellent motorcycles today. Manufacture of the D1 started in 1948 and ceased in 1964 to make way for more refined models; overall Bantam manufacture was stopped in 1971 after a run of 23 years. Increasing competition from Japanese motorcycles proved difficult to counter and effectively killed off the Bantam together with many other established motorcycles which could not compete in price or performance.

The manufacturer who made the Bantam, BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) was originally a gun factory in Birmingham that opened in 1861 and became a massive enterprise. Of course, this company does not exist anymore, unlike its main rival/stablemate Triumph, which still continues the British tradition, making excellent motorcycles today. Manufacture of the D1 started in 1948 and ceased in 1964 to make way for more refined models; overall Bantam manufacture was stopped in 1971 after a run of 23 years. Increasing competition from Japanese motorcycles proved difficult to counter and effectively killed off the Bantam together with many other established motorcycles which could not compete in price or performance.

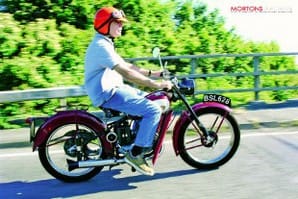

The authors’ model was built in late 1962 and was among the last of the D1s which had become fairly refined compared to the early models and included the luxury of having a battery, chrome rims and finished in maroon paint. The review model featured plunger suspension which was an improvement from the earlier rigid system in which the rear sprung seat and pneumatic tyres were the only defence against road undulations.

The dealer who sold this particular motorcycle was the then well known establishment of Wheeler in Epsom, whose name is impressed on a brass dealership plate which still retains its proud position on top of the rear mudguard: ‘Supplied by Wheeler Motors, West Waterloo Road, Epsom. Phone 450/6’. William Arthur Wheeler, from whom the term ‘Wheeler Dealer’ was acoined, was a successful motorcycle racer and engineer. He was born on August 5, 1916, in Epsom Surrey and died on June 9, 2001.

Many original accessories that were fitted to the bike still remain including: legshields, battery (shell only), cover horn and road tax licence holder. The chronometric speedometer still displays the original mileage (around 20,000 miles). An original small motorcycle ‘AA’ badge has been added and affixed to the legshields to provide a contemporary flavour. The front and rear numberplates are also the originals, albeit with new registration numbers.

Many original accessories that were fitted to the bike still remain including: legshields, battery (shell only), cover horn and road tax licence holder. The chronometric speedometer still displays the original mileage (around 20,000 miles). An original small motorcycle ‘AA’ badge has been added and affixed to the legshields to provide a contemporary flavour. The front and rear numberplates are also the originals, albeit with new registration numbers.

Parking regulations in the UK stipulated the use of a parking light; early versions of this motorcycle, which used direct lighting, required the owner to fit a dry cell cycle lamp to be added for this purpose. This model was fitted with a battery providing improved lighting, the six volt electrics are now considered very inefficient, but perhaps it is not for us to judge vintage vehicles by today’s standards. The companies of Lucas and Wico-Pacy made the electric components that were used for ignition and lighting. Early versions of the D1 used a pneumatic horn with a bulb placed conveniently on top of the steering yoke; as a refinement an electric horn was later adopted.

The air cleaner is a simple device which incorporates the choke. When required for starting the motor, the air flow is restricted via the choke lever, located at its base, to provide a richer mixture. A ‘tickler’ was also provided to stimulate fuel flow into the float bowl priming it for starting.

Bolt-on legshields and rear bumper bars which are quite rare items today and desirable for the enthusiast. A handy bicycle pump was discreetly fitted underneath the right side of the fuel tank. A duel seat was available which could be fitted in place of the luggage carrier-rack. Folding rear footrests were available too. A simple tool kit which was contained in a compartment on the left of the bike. The chrome fuel tank cap incorporated an oil mixture ratio measuring cup of 32:1, marked on the cap reads: ‘2 MEASURES OIL PER GALLON PETROL’.

Bolt-on legshields and rear bumper bars which are quite rare items today and desirable for the enthusiast. A handy bicycle pump was discreetly fitted underneath the right side of the fuel tank. A duel seat was available which could be fitted in place of the luggage carrier-rack. Folding rear footrests were available too. A simple tool kit which was contained in a compartment on the left of the bike. The chrome fuel tank cap incorporated an oil mixture ratio measuring cup of 32:1, marked on the cap reads: ‘2 MEASURES OIL PER GALLON PETROL’.

Conclusion

Although by today’s standards Bantams are slow and vulnerable on the larger roads, with their 4bhp power output, they are still a joy to ride and the atmosphere of yesteryear’s motorcycling is well worth experiencing. The maximum speed is quoted as 45mph, although 52mph was recorded while the authors conducted their own basic road tests; however, the Bantam is happy to cruise economically at 40mph for sustained periods. The speedometer needle has the peculiarity of jumping in increments while recording the speed. The legshields provide some weather protection from ankle to knee and act as a form of crash-bar in an accident.

The authors found the geometry of the gear change lever awkward to operate when the right foot was placed on the foot rest. The bike was found to handle well, the brakes and suspension adequate for its speed – although the single seat could have been a little wider and softer sprung. Due to its low compression 6.5:1, the bike kicks over easily and is no problem to start. A peculiarity of this bike is its loud induction noise which is louder than that of the exhaust. Oddly there is no provision for an ignition cut-off, therefore the throttle has to be left forward to let the idling slow down until it stops; a rather irritating quality which means that the throttle must not be neglected at traffic lights. The silencer, not being a sealed unit can be easily dismantled allowing the baffles to be de-coked, a perpetual problem with early two-strokes. This is due to the oil/petrol mixture causing a carbon build-up.

Over the years many people derided this bike, calling it lacklustre and boring, but it is now looked on with affection and a special resonance by the older generation and those who appreciate historic vehicles. These humble machines were durable, made to last and will still be on the roads after many modern bikes are languishing on the scrapheap pending recycling. Enthusiasts will never let it fade into obscurity. These motorcycles were made to be simple and most of the maintenance could be carried out by the owner – this is not so easy on modern motorcycles. Many spare parts often newly made are available for this popular bike. Even today a Bantam in reasonable condition can be purchased at a relatively low price as there are several still around – a testament to its build quality and design – good old British engineering! ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.