Now, I love little lightweight motorcycles. I always feel much more at home in the saddle of a ‘tiddler’. I think it’s a psychological thing as much as anything; I like to be able to feel fully in control, and being able to put both feet comfortably on the ground also helps.

These ‘rules’ especially apply when riding someone else’s motorcycle. But I also appreciate that small-scale machines aren’t going to perform as well as their bigger capacity brethren. Of course, there are notable exceptions, but while the old adage that a ‘good little ’un beats a bad big ’un’ rings true, a ‘good big ’un beats a good little ’un’ is also equally true. So, naturally, many aspire to the good big ’un, often ending up with a bad big ’un, and forsake a good little ’un on the way!

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

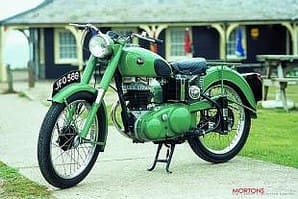

Apologies for all that convoluted introduction, but I’m just trying to put Bob Wilkinson’s C10L into some sort of context. Machines like the C10L are often overlooked in the scramble for more heavyweight machines, but having spent some time in the saddle of the side-valve 250 I’m more convinced than ever of the benefits of a good little ’un.

Apologies for all that convoluted introduction, but I’m just trying to put Bob Wilkinson’s C10L into some sort of context. Machines like the C10L are often overlooked in the scramble for more heavyweight machines, but having spent some time in the saddle of the side-valve 250 I’m more convinced than ever of the benefits of a good little ’un.

Bantam-derived

In truth, a post-WWII side-valve 250, with plunger rear springing and Bantam-derived telescopic front forks, won’t set the pulses of many enthusiasts racing. That’s not being derogatory about the little Beesa – it’s just being truthful. A lot of classic enthusiasts are keen to buy into the whole nostalgia thing, often buying now what they lusted after but couldn’t afford when they were younger, hence the premiums for Vincents, Bonnies, Goldies etc – aspirational motorcycles, then and now.

A C10L has never been (and in truth never will be) an aspirational motorcycle in the conventional sense of the word. I very much doubt schoolboys doodled pictures of C10Ls in their homework jotters, as they undoubtedly did of Manx Nortons, Vincent Black Shadows and BSA Gold Stars. Even if they were a particularly strange child who longed for a 250cc Beesa in idle moments during geography lessons at school, it would’ve been the ohv – and so positively sporting! – C11 which was top of the list.

Of course, for many of these schoolgoers who managed to acquire a motorcycle when they left school, a C10L was exactly he sort of thing that they landed. So, up and down this country and others too, C10Ls – often having served their first owner, normally some sort of commuter faithfully for a few seasons – passed into the hands of young lads with heads full of Goldies and Rapides. And these same young lads duly thrashed, abused and inevitably broke, then mended and broke again, and again, and again, their C10s and the like until eventually the lightweights cried enough and were fit for no more than the scrap man.

So, that’s the irony. All those Goldies, Rapides, Shadows and the like – they’re everywhere at any classic event up and down the country. But a C10L – hands up who can remember seeing one at a classic show? Let alone more than one… quite simply, they’re a rarity now, falling into that category of “I haven’t seen one of those for years…”

The shame is, having ridden Bob’s, it’s a pity there aren’t more of them about because – judging by this example – they’re really very good.

Bob Wilkinson bought this example on the auction website eBay, for £1300. Registered on 22 December 1955, it is one of the last C10Ls made. Bob, an ex-fireman who was in the service for 20 years, fancied a runabout that wouldn’t depreciate, so in early 2005 he took the plunge and bought the diminutive side-valve. It’s a decision Bob hasn’t regretted for one moment – indeed, such has his enthusiasm been stoked that since buying the baby Beesa, Bob has joined the BSA OC and become an enthusiastic member of East Sussex BSA OC and added a very smart A10 cafe racer to his stable.

Bob admits he hasn’t done much to the C10 since its acquisition. With it came receipts totalling £2000, indicating that it had undergone a thorough restoration. Says Bob, “The C10L attracts lots of attention – though a lot of people do think it’s a Bantam, due to the colour.”

Bob admits he hasn’t done much to the C10 since its acquisition. With it came receipts totalling £2000, indicating that it had undergone a thorough restoration. Says Bob, “The C10L attracts lots of attention – though a lot of people do think it’s a Bantam, due to the colour.”

And its proportions feel very Bantam-esque, too. It’s funny really – the C10L feels much more similar in size from the saddle to its contemporary 100cc (or 125cc) smaller Bantam stablemate, than its 100cc bigger B31 brethren. It would be easy to think you were settled on a Bantam – but never would it be mistaken for a B31. The C10 is much slimmer and smaller than the B31; feels closer to the ground and the handlebars seem narrower, too.

Setting off, I must admit I was expecting to be a bit underwhelmed. I was expecting a steady, slow plodder, flexible with an unhurried but essentially pleasant nature. The C10L delivered all these things, but it was also a whole lot better than I expected. If it feels from the seat – and indeed looks from the street – a bit Bantam-esque, then I have to say that the performance delivered reminded me a lot more of my old B31 rather than a contemporary Bantam. Now, perhaps this is a particularly good example, but I was astounded by its liveliness and the amount of fun I was having in the saddle.

Stopping to compare notes, Bob backed up my experiences and confessed that he doesn’t give the C10 an easy time on club runs by any measure, often running with much bigger capacity machines and the little C10 hasn’t complained at all.

I set off again, really enjoying the little Beesa’s willingness to perform. Through a couple of sweeping S-bends, it performed admirably, though the combination of sprung saddle and plunger rear springing did mean a bit of ‘see-sawing’ but that’s probably more to do with the saddle than the suspension. It wasn’t by any means offensive and soon would become just part of the ride, as the rider acclimatised.

Braking was as would be expected – nothing exceptional but no worse than any other 50s offering, while the gearbox was uncomplaining as it was given a thorough work through with all the stop-starting that a photoshoot entails. The clutch had begun to get a tiny bit hot-and-bothered with all the starting and stopping, but that’s no reflection on the clutch – more on the workload it was put under. As soon as we got away from the stop-start work, the clutch was fine again.

I set off for a bit of a ride around the roads near Beachy Head where we were taking the pictures – incidentally, on the same bit of road BBC’s Top Gear apparently do many of their car tests – and the C10 continued to perform much better than expectation had led me to believe. The undulating roads, with a few hills, tight bends and relatively steep drops, offered a thorough workout.

Obviously, this is only a little engine, so the gearbox had to be worked, but I was surprised at the amount of work which could be undertaken in (appropriately for the road!) top gear. I must confess, the performance of the C10L had not only surprised me, but impressed me too. By the time my ride was drawing to a conclusion, I was full of admiration for the little quarter-litre workhorse, and it reinforced my belief that classic motorcycling can still be a great fun pastime for comparatively little outlay. And you’ll stand out from the crowd!

Of course, the C10L was the last in a long and proud line of side-valve 250cc models, which did much to cement BSA’s place as the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer. The rock upon which much of their empire was built was the humble quarter-litre commuter. It all began with the 1924 launch of the (initially) two-speed 120mpg Model B, instantly known as the ‘Round Tank’ due to its marrow-esque fuel container. The Round Tank was to be a range mainstay, with thousands sold to those who appreciated quality at an affordable price. In the first year alone, 5000 were sold to satisfied customers, and just four years later, production stood at 35,000. Allied with the other solid side-valve singles in the range, plus a worthy ‘big’ V-twin and then the Slopers and the odd sporty ohv single too, BSA had a solid base on which to build. But it was the Round Tank which underpinned the whole operation.

Of course, the C10L was the last in a long and proud line of side-valve 250cc models, which did much to cement BSA’s place as the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer. The rock upon which much of their empire was built was the humble quarter-litre commuter. It all began with the 1924 launch of the (initially) two-speed 120mpg Model B, instantly known as the ‘Round Tank’ due to its marrow-esque fuel container. The Round Tank was to be a range mainstay, with thousands sold to those who appreciated quality at an affordable price. In the first year alone, 5000 were sold to satisfied customers, and just four years later, production stood at 35,000. Allied with the other solid side-valve singles in the range, plus a worthy ‘big’ V-twin and then the Slopers and the odd sporty ohv single too, BSA had a solid base on which to build. But it was the Round Tank which underpinned the whole operation.

After a few years, the Round Tank De Luxe morphed into what was instantly known as the Wedge Tank, on account again of its fuel tank shape. The ‘wedge’ was otherwise basically unchanged, sporting the same basic, 250cc side-valve engine. By now all variants had a three-speed gearbox and drum brakes fore and aft.

With changing fashion, the 250cc side-valve gained a saddle tank, and remained in the range, for much part unchanged from its introductory specification. Into the 30s, the 250cc side-valve was listed as the B model – with the year and the number ‘one’ following. In 1936, the 250cc side-valve became the B1, then the B20 the year after.

In 1938, a C range was launched for the first time, to run alongside the B models, with the side-valve C10 and – following later – ohv C11. These were even cheaper than the Bs and both the C10 and C11 boasted coil ignition and costing under £40. Clearly aimed at the budget, non-motorcycle-enthusiast end of the market, nevertheless they were well finished and became instant successes, adding to BSA’s enviable reputation for producing quality wares at affordable prices. The C10 had pedigree too, having been designed by the respected duo Val Page and Herbert Perkins. Apparently, Page set down the brief, with Perkins responsible for the detailing. On launch, the C10 – with little chrome plating and a green-painted fuel tank – was listed at £37-10s.

Post-WWII, the two C models both reappeared, listed for the 1946 season. They were initially indistinguishable from the pre-war models, but for 1947 both gained telescopic forks. In 1951, plunger rear springing was first offered as an option, though in 1954 came the major redesign. The C10 was rechristened the C10L – with L standing for lightened. The engine unit was transplanted into what was basically a D3 Bantam Major frame; hence riding Bob’s example feels so Bantam-esque. The C10L was clearly aimed at budget motorcyclists, presumably those who didn’t want a two-stroke. But, as evidenced by this example, it was still very much a well-built motorcycle.

Post-WWII, the two C models both reappeared, listed for the 1946 season. They were initially indistinguishable from the pre-war models, but for 1947 both gained telescopic forks. In 1951, plunger rear springing was first offered as an option, though in 1954 came the major redesign. The C10 was rechristened the C10L – with L standing for lightened. The engine unit was transplanted into what was basically a D3 Bantam Major frame; hence riding Bob’s example feels so Bantam-esque. The C10L was clearly aimed at budget motorcyclists, presumably those who didn’t want a two-stroke. But, as evidenced by this example, it was still very much a well-built motorcycle.

The C10L – by now an aged anachronism – was finally deleted from the range for the 1957 season. BSA were on the cusp of a brave new world for 250s, with the unit C15 only a season away, and the old C10L had served its purpose and its time was up. Not a passing lamented by many, if truth be told, but it had served thousands well over the years, taking them to and from work and offering thrifty independence. With learners soon restricted to 250cc too, it offered many youngsters their first motorcycle at a low price – and that’s why so few still exist. It’s a shame really, because, all things considered, they’re a good little bike and still make a fine commuter today and one that isn’t going to depreciate – plus is a bona fide rarity. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.