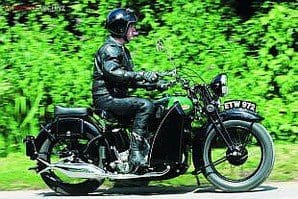

The British heavyweight side-valve V-twin reached its zenith in the 1930s, with models like this G14 BSA proving popular with sidecar men especially. Long of wheelbase and of stroke, the big twins provided plenty of lazy power, delivered with the minimum of fuss – and revs – in a smooth, continuous and unthreatening wave. Gearchange was normally by hand, but that didn’t matter as speed wasn’t of the essence – changing gear was barely necessary anyway, with the big twins able to lope from low speeds, with the ignition retarded, up to their cruising speed – with ignition advanced on the way – in top gear.

The V-twin had of course been a popular engine layout from the Pioneer days and remains one today. In the 1930s, though, it was the ultimate development of the ‘old style’ side-valve V-twins that were in vogue, with the British factories anyway. At the top end of the scale was the Brough Superior 11-50, while the ‘lower order’ were catered for by the likes of the Royal Enfield KX, the Matchless Model X and the G14. The heritage of the BSA G14 and its ilk could be traced back to the veteran era, but by the 1930s, the big twins were a bit more modern – but not too modern, though.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Post WWII the V-twin as sidecar tug and ‘lolloping’ crusier all but disappeared from the UK makers’ line-ups, with the only British V-twin on the market the Vincent – which was nothing like the antiquated, traditional side-valvers of the 1930s. Over in the USA, though, the G14 ‘style’ remained – and indeed, to an extent remains – popular, to this day, as ‘Big Chief’ Indians and Harleys continued to sell.

British manufacturers though had left behind the ‘grand tourers’ of old and would never return to that market, with the big UK makers instead preferring to go down the road of ‘sportsters’, more about performance than ‘cruising’. Indeed, the Americans pretty much had the ‘cruiser’ world sewn up – though perhaps Moto Guzzi could stake a late 60s/early 70s claim – until the Japanese decided that they’d like a piece of (Momma’s ol’ apple) pie. So, the cruiser market once again had makers from different countries competing in it – and then the Brits joined the fray, with rejuvenated Triumph, though with an inline triple in their Rocket III, rather than a V-twin. But the sentiment was the same.

British manufacturers though had left behind the ‘grand tourers’ of old and would never return to that market, with the big UK makers instead preferring to go down the road of ‘sportsters’, more about performance than ‘cruising’. Indeed, the Americans pretty much had the ‘cruiser’ world sewn up – though perhaps Moto Guzzi could stake a late 60s/early 70s claim – until the Japanese decided that they’d like a piece of (Momma’s ol’ apple) pie. So, the cruiser market once again had makers from different countries competing in it – and then the Brits joined the fray, with rejuvenated Triumph, though with an inline triple in their Rocket III, rather than a V-twin. But the sentiment was the same.

Now, the ‘cruiser’ market is one of the biggest and most profitable sectors of the motorcycle market worldwide, although you’d be hard pushed to tell that from reading the modern UK motorcycle Press, particularly the most-popular weekly… but the truth of the matter is, cruisers are big business and they cost big money.

Of course, though, in the 1930s machines like the BSA G14 weren’t looked upon as ‘cruisers’ for pootling around on, on a sunny Sunday morning – indeed, they were more likely to be seen groaning under the weight of a heavily laden sidecar, working for a living, rather than a perk of good living. It’s only retrospectively that we can tag the G14 a cruiser, really, but it has many of the attributes – lazy torque, long wheelbase, pulled back handlebars, bulbous tyres, plenty of chrome and a low seat height – of a modern cruiser.

This G14 has been restored by well-known Hertfordshire restorer Robin James, whose work is no stranger to the pages of this magazine. The G14 belongs to Monmouthshire man Rob Griffiths, who is a classic scrambler of some repute, campaigning heavyweight British tackle.

Robin knew Rob from the classic scrambles world – Mr James was a handy scrambler too, who has recently sold his last remaining, well developed Goldie scrambler – and Robin takes up the tale.

“Rob showed up out of the blue with the G14, it was in a shocking state. It was what you’d call a proper barn find, in that it’d spent years stood in a barn covered with straw.”

The big Beesa had belonged to Rob’s father, who’d used it as a sidecar outfit, before it passed to young Rob who honed his scrambles technique by racing the big twin round and round fields. The whole motorcycle had suffered considerably, not least the crankcases, which had never had the mud which Griffiths Junior’s outings had covered them with, washed off.

Says Robin: “It was very worn out, the crankcases were heavily corroded – in fact, if you look closely, you can still see traces of the damage done to it.”

On its deposit in his workshops, Robin closely inspected the BSA, working his way through it and making some observations along

the way.

“When you look at it closely,” says Robin, “Its 1920s heritage is immediately apparent, right down to the exposed valves and the like.” The valves receive no lubrication, either, apart from that supplied by taking off the cover and giving them a ‘squirt.’ The big Beesa also has items like interchangeable wheels, which hints at its expected role of sidecar tug.

Heavy flywheels

Heavy flywheels

Though the 1000cc motor probably produces no more than 8/10bhp, it has lots of torque, thanks in part to the immense, enormously heavy flywheels. There is a four-speed gearbox, which is hand-change (in fact, the gearbox is the standard BSA four-speeder, turned on end to fit in the frame). Robin doesn’t rate the gearbox – all machines are thoroughly run-in and fettled before delivery so he puts in plenty of miles on them himself – saying that the best technique is to, “Give it a big handful in bottom then go straight through to top…”

Overall the BSA was in a poor condition, with the cycle parts having suffered just as much as the crankcases, thanks to their ‘hard work’ trekking round Welsh fields. Rob was keen to re-fit the legshields, which were very battered – in fact, in such disrepair that they could only be used as patterns by tin-bashing wizard Terry Hall. Terry was also responsible for making the new tool boxes, as well as making good the dented and disfigured petrol tank and the pressed-steel chaincase. Terry’s work is exemplary.

One of the slightly more unusual features of the G14, is its frame. The machine features a forged-steel backbone to its frame, with the head-lug alone weighing a whopping 35lb! Also forged, were the top-beam for the frame and the seat support too. Forgings have not often been used on motorcycles, apart from for con-rods, though forged components are acknowledged to be stronger than cast. It was a practice oft used in gun manufacture, which of course was BSA’s original business.

With the BSA running and warmed up, it was time for me to get acquainted with it. “Right,” says Robin, “Just remember one thing. With the legshields fitted, when you’ve got your feet up on the footboards, you can’t just take them off.”

What he means is that, the design of the footboards is such, that the rider puts his feet ‘inside’ them, as the legshields bolt to the sides of the footboards as well as the front. I’m sure this is something one would quickly get used to, but riding someone else’s freshly – and indeed expensively – restored motorcycle, the thought of an embarrassing, ungraceful and potentially expensive flailing tumble to the ground didn’t fill me with too much confidence. Also, once both feet were ensconced within their surrounds, operation of the rear brake lever became nigh-on impossible.

Rider's heel

The rear brake is operated by a pedal at the rear of the left-side footboard, supposed to be operated by the rider’s heel. However, I found that the footboards meant that it was awkward to get to and one would have no confidence in an emergency of being able to get there in time… so I settled on an ungainly ‘one foot forward, one foot back’ stance, with my right foot inside the leg shield and the front of my left foot ‘balanced’ on the very back of the footboard, behind and outside the leg shield…

Still, it wasn’t too bad though in practice I found it easier and more comfortable to ride with both feet behind the legshields, which was partly for ease of ‘footing’ but also because it was a boiling hot day and it was, to say the least, ‘warm’ on the legs ensconced within the enclosed panelling.

Still, it wasn’t too bad though in practice I found it easier and more comfortable to ride with both feet behind the legshields, which was partly for ease of ‘footing’ but also because it was a boiling hot day and it was, to say the least, ‘warm’ on the legs ensconced within the enclosed panelling.

The long swept back bars give a tiller feeling to the steering, more early 20s than late 30s, though it affords an ideal riding position for gently cruising. The wheelbase feels long from the saddle – as it indeed of course is. The BSA features twin twist grips – the right-hand one controls the throttle in a normal manner, while the left one is the ignition advance retard. Robin’s advice was to use them in tandem with both being twisted towards the rider under acceleration, which further reducing the need for gear changes. When rolling off the throttle, ‘roll off’ the ignition too, thereby meaning there’s no need for a downward change.

Not having to change gear adds to what is overall a relaxed and enjoyable riding experience. Loping along, with the big unstressed V-twin engine happily chugging away, then it all starts to make sense why this ‘cruising’ lark has become such an important and popular aspect of motorcycling. An unstressed motor, leads to unstressed motoring. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.