Rider Bill Johnson is as slim as they come. Yet the light-alloy monocoque cockpit fits him as closely as his underwear. A course of muscle building and he'd be in trouble.

Elbow width is a bare 20in. The most Spartan wire padding keeps his backside only 3in off the Utah salt, while the quick-release glass-fibre cockpit cover grazes the top of his helmet. Three small clear-plastic panels give him a view to the front and sides. A lap strap fastens him down. To cushion the kick of acceleration, backrest and headrest are thinly padded.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Between the rider's knees is a vertical column, at the top of which is pivoted the handlebar. The ends are bent down very steeply and measure just 15in across. Steering lock is limited to a few degrees. The clutch lever on the left is fitted upside down so that it points skyward. More unusual still, a front-brake lever is used instead of a twistgrip to operate the throttles. (There is no front brake.)

When changing gear Johnson drops his right hand straight off the bar on to the positive-stop lever on the side of the cockpit. A similar lever on the left releases the spring-loaded struts that project from behind the seat to support the machine when it comes to a standstill.

When changing gear Johnson drops his right hand straight off the bar on to the positive-stop lever on the side of the cockpit. A similar lever on the left releases the spring-loaded struts that project from behind the seat to support the machine when it comes to a standstill.

Other cockpit controls are a lever on the right-hand side connected to the fuel cock, a magneto switch on the steering column and a rear-brake pedal on the centre line, where it can be operated by either foot or both. In a panel directly above the steering column is the rev-meter.

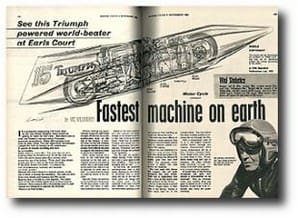

Basically, Dudek's streamliner can be considered in three parts. The 4ft-long cockpit is the middle part and there is light-alloy bulkhead at each end of it.

Bolted to the front bulkhead are two tubular triangles bridged at the forward apex by a cross tube carrying the front wheel. Made from an obsolete Triumph rear spring hub, this wheel incorporates hub-centre steering. Pin-jointed track rods pass back through the bulkhead to the handlebar.

The 19in steel rim carries a ribbed Dunlop Track Racing tyre with a tread depth of only 1mm (0.040in). There is no springing front or rear.

At the front, the reinforced aluminium-alloy shell is cone shape, blending at the cockpit to cylindrical with a tunnel along the top to fair the rev-meter panel and merge with the cockpit cover. On the underside of the nose a divided spat deflects air away from the front-wheel opening to prevent pressure from building up inside and lifting the nose.

The shell has more affinity to supersonic rocket practice than for the streamline shapes usually used for subsonic speeds (i.e., below 750 mph).

Behind the rear bulkhead is a structure made of steel tubing, light-alloy plate and angle strip. Besides housing the Bonneville engine, gearbox and rear wheel, this structure incorporates a safety roll loop behind the headrest.

The fuel tank sits above the engine, the oil tank alongside the rear wheel. That has a light-alloy rim and a tyre of the same size and pattern as the front.

Access to the engine is gained through hinged doors in both sides of the fairing. Scoops in these doors lead air to the cylinder block. The rear half of the block is closely cowled to circulate the air through the fins.

With a compression ratio of 11 to 1, the engine breathes alcohol vapour through two massive hose-mounted Amal racing carburettors fed by a float chamber between them. Tract length from carb mouth to valve head is 12in. Thirty-three inches long and 1.5 in diameter, the plain exhaust pipes discharge through cutaways in the shell sides. Ignition is by a Lucas racing magneto.

A small hole in the fairing alongside the gearbox allows a kick-starter to be inserted! Not so strange when you realize that top gear is about 2½ to 1, and so bottom gear is just over 6 to 1 – which is hardly the ratio for push-starting! ![]() View original article

View original article

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.