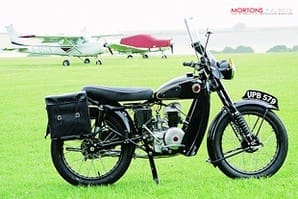

I was still hauling this charming little Franny Bee onto its stand, in readiness for the static photographs, when a bystander came bounding over. “I haven’t seen one of those since 1964,” he said excitedly, “our vicar used to have one just like that!”

I’ve always distrusted personal reminiscences since a chap told me that he’d once owned a bike just like my Greeves, except that Villiers had made both the engine and the frame! But this time the story rang true. The FB Falcon is just the sort of machine you’d expect a parsimonious parson to chose; it’s pretty in a plain sort of way, and it’s powerful enough to be practical without being pretentious.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

All right, I’ve run out of ‘P’s’ now, so we’ll get down to facts, because this is a businesslike sort of bike, and it was actually an essential part of its original buyer’s business. Remarkably, he was the father of the present owner, and the 1954 Falcon has been in one family’s possession for than half a century.

“My father ran a fish shop in Kingston, London,” John Gerry tells me, “while we lived a few miles further south in Chessington, and he bought the Falcon to get to and from work. At about that time, though, I’d become an apprentice pattern maker in Wimbledon, and I was dead keen to have a bike like my contemporaries, so we worked out a plan whereby dad and I could share the Francis-Barnett. He used to go to work on the bus, while I’d ride in on the Falcon. Then, after I finished work, I’d ride it round to Kingston, and leave it with him while I ran home. Later, after dad shut up shop he’d ride home with the day’s takings, and that’s why he fitted the panniers, to carry the money in!” Luckily, John was keen on athletics, but I guess that many teenagers would have thought that running a few miles was a fair swap for being able to turn up for work on a brand-new bike.

“My father ran a fish shop in Kingston, London,” John Gerry tells me, “while we lived a few miles further south in Chessington, and he bought the Falcon to get to and from work. At about that time, though, I’d become an apprentice pattern maker in Wimbledon, and I was dead keen to have a bike like my contemporaries, so we worked out a plan whereby dad and I could share the Francis-Barnett. He used to go to work on the bus, while I’d ride in on the Falcon. Then, after I finished work, I’d ride it round to Kingston, and leave it with him while I ran home. Later, after dad shut up shop he’d ride home with the day’s takings, and that’s why he fitted the panniers, to carry the money in!” Luckily, John was keen on athletics, but I guess that many teenagers would have thought that running a few miles was a fair swap for being able to turn up for work on a brand-new bike.

Anyway, the Francis-Barnett served father and son well, and John passed his test on it. “I failed the first time,” he admits, “as I slid off on ice on the way to the testing station and, having narrowly missed being run over, my mind wasn’t really on the job when I got there.”

John subsequently got called up for National Service, and acquired a BSA B31 for travel home and weekend outings. An A7 Shooting Star followed, as did marriage, a family, and a Watsonian sidecar. “My wife sat on the pillion and the carrycot just slid into the chair,” grins John, “but then, of course, we got a car, and it was goodbye to motorcycling for quite a few years.”

Mr Gerry Senior, meanwhile, carried on using the Falcon intermittently until about 1970, after which it was laid up in the corridor beside the Wiltshire house to which John had moved. He promised himself that he’d restore it when he retired, but his first retirement was followed by a spell doing worthwhile work in support of rural industries, so there was a bit of a delay. On the credit side, that job produced some very useful contacts among local craftsmen and engineers.

Mr Gerry Senior, meanwhile, carried on using the Falcon intermittently until about 1970, after which it was laid up in the corridor beside the Wiltshire house to which John had moved. He promised himself that he’d restore it when he retired, but his first retirement was followed by a spell doing worthwhile work in support of rural industries, so there was a bit of a delay. On the credit side, that job produced some very useful contacts among local craftsmen and engineers.

The restoration took the best part of three years, with John fitting it in between household responsibilities. “I didn’t go at it full-tilt,” he says, “I just put in an hour now and again, when I could spare the time.” The great advantage he had was that the Francis-Barnett was absolutely original and intact, although all the rubber and fabric parts were pretty moth-eaten. John did some of the paintwork himself, and had the frame powder coated by Wessex Metal Finishers.

The metal components were all reusable, even the wheel rims that usually bear the brunt of corrosion. They were originally painted rather than chromed – presumably because of the nickel shortage caused by the Korean War rather than as an economy measure, since there is no penny pinching elsewhere – and their rebuilding with stainless steel spokes was entrusted to local company Brickwood Wheel Builders, who also handled their re-finishing and lining. The repainting of the petrol tank was done by JBS and the elegant gold pinstriping wouldn’t look out of place on a much more prestigious machine than the little Franny Bee.

The point is that Francis-Barnett evidently didn’t see themselves as makers of cheap ride-to-work bikes. Their Falcon cost 50 per cent more than a simple commuter like BSA’s D1 Bantam, and was obviously intended to be a quality lightweight for people who simply didn’t want the weight and complexity of a four-stroke engine. For instance, the 1954 Falcon actually cost more than that year’s 250cc side-valve C10 BSA, but Falcons had featured swinging arm suspension since 1951 (when production started alongside the previous, rigid-framed, version) while the Beeza made do with plunger suspension until production stopped in 1957.

Other classy – and costly – features include generously valanced mudguards and a chronometric speedometer. There’s even an ammeter to keep an eye on the battery charging, and you have to remember that many lightweights didn’t even have a battery in those days, instead relying on feeble and intermittent direct lighting.

Other classy – and costly – features include generously valanced mudguards and a chronometric speedometer. There’s even an ammeter to keep an eye on the battery charging, and you have to remember that many lightweights didn’t even have a battery in those days, instead relying on feeble and intermittent direct lighting.

So what is this stylish lightweight like to ride? Well, with one reservation, which I’ll deal with in a moment, it’s a real pleasure. And if you were expecting me to say that the reservation concerns the Villiers power unit; you’d be half right. Now a lot of people decry Villiers’ products, and I’ll admit that they tend to be mechanically noisy, but that’s partly because they were designed to have generous clearances, and the benefit is that they carry on running even when those clearances increase to the point that would spell doom for a more sophisticated motor.

And while the Villiers 8E engine fitted to the Falcon won’t excite speed freaks, I, for one, appreciate the way it does its business at such modest revs that I’m not discouraged from using what power there is. Additionally – because the aluminium ‘saucepan’ on the right-hand side of the engine houses a brass flywheel of monumental dimensions – the 8E continues pulling sturdily at engine revs that would be below stalling speed for a modern stroker. Even if the engine cut out, the flywheel’s momentum would probably carry you as far as the next hill before you noticed!

The flywheel also whizzes the magnets around internal coils to act as a magneto, but that’s not the drawback I’m thinking of, either. I know you’ve seen people cursing Villiers motors that won’t start because of inadequate sparks, but you see exactly the same thing with bikes using conventional magnetos, and nobody condemns an entire class of engine because of it. Provided the magnets and coils are up to the mark, the Villiers flywheel magneto is an effective and reliable piece of kit.

The flywheel also whizzes the magnets around internal coils to act as a magneto, but that’s not the drawback I’m thinking of, either. I know you’ve seen people cursing Villiers motors that won’t start because of inadequate sparks, but you see exactly the same thing with bikes using conventional magnetos, and nobody condemns an entire class of engine because of it. Provided the magnets and coils are up to the mark, the Villiers flywheel magneto is an effective and reliable piece of kit.

No, the engine isn’t a problem, but the three-speed gearbox definitely is. In fact it’s only tolerable because of the motor’s forgiving nature, and even then the yawning gaps between the ratios mean that you often have to choose between slogging the motor or screaming it. Villiers obviously kept on making three-speed gearboxes for road bikes – years after they’d developed a four-speed box for their competition motors – because of demand from their customers. But I’ll never understand why manufacturers continued specifying three-speeders once the four-speed box became available. Obviously it was cheaper, but standardization on the better unit could well have brought economies of scale that would have reduced the price differential to an acceptable level, and what a difference it would have made!

A four-speed gearbox would have cemented Francis-Barnett’s obvious aim of being a quality producer, whereas all they did was to make it an optional extra on post-1954 Falcons. Their failure to adopt it certainly wasn’t because they were reluctant to produce improved models. On the contrary, a bewildering number of Falcons were made over an 18-year period until production stopped in 1966.

Francis-Barnett used a logical, but rather unusual system for designating their models. All post-WWII Francis-Barnetts in the 200cc class were called Falcons, but instead of entitling successive variants MkI, MkII and so on, they became part of a sequential numbering system covering all of the models in the range. So, the Falcon 67 featured here was the successor to the Falcon 58 (1951-53), and in between came a couple of smaller engined Merlins (Models 61/63) and the Kestrel 66, not to mention the Falcons 60/62, 64 and 65, which were all intended for off-road use. I mention this, not to confuse you, but to prove that Francis-Barnett were not quite the staid concern you might have thought. The 60 and 62 were triallers – so no great surprise there – but the 64 was a scrambler, which does seem a bit at odds with the Francis-Barnett image.

Most remarkable, though, was the Falcon 65, which was nothing less than a road going trials machine. In modern terms that equates to a trail bike, and not many companies would have known what one was in 1953, let alone considered producing one.

Most remarkable, though, was the Falcon 65, which was nothing less than a road going trials machine. In modern terms that equates to a trail bike, and not many companies would have known what one was in 1953, let alone considered producing one.

And FB off-road bikes were remarkably successful, with one – ridden by Bill Lomas – actually having the distinction of being the first small two-stroke to win a national trial. So I’m not at all surprised to find that the cycle parts of John Gerry’s road-going Falcon work really well. Bend-swinging is an utterly undramatic business, and – since the brakes are well up to the job – all of the engine’s modest power can be used with abandon. This is in sharp contrast to some lightweights I’ve ridden, and shows the quality of John’s restoration. He dismantled, checked and refilled the rear suspension units himself, and had the somewhat corroded front fork stanchions refurbished by Dan Force. The result is supple suspension that gives a very good combination of comfort and control.

Even the dualseat is comfortable. After the bike’s long lay-up, it was natural to find its seat beyond repair, but John has made an excellent metal base and had it re-upholstered locally. And another of the contacts he made in his work with rural industries fabricated the superb panniers in leathercloth, while John used the same material to make the HMF screen’s apron.

I just love the period look of the screen and legshields, and – when the heavens opened during my test ride – I found that they actually do their job very well. And the panniers are equally well designed, fitting snugly without rattles, yet being truly quickly detachable. These accessories have been with the bike since the 1950s, as has what I imagine is the only significant non-original feature – the handlebars. They are ‘Norton straights’ with clamp on levers, whereas original fitments would have been semi-raised with welded lever pivots. “That’s a legacy of falling off on my way to take my test,” grins John, “the only damage was to the handlebars, so we had to replace them, and during the restoration I copied the same style.” Well, why not? It’ll give the rivet counters something to criticise, because there’s very little else to complain about (except that gearbox!).

Oh yes, John also admits that the tyre pump is a modern pattern type, but that’s only because the spring in the original (which he still has – naturally) no longer holds it securely in place, and the genuine battery case now holds modern cells from Burlens.

Oh yes, John also admits that the tyre pump is a modern pattern type, but that’s only because the spring in the original (which he still has – naturally) no longer holds it securely in place, and the genuine battery case now holds modern cells from Burlens.

It’s no surprise that many enthusiasts choose to restore the type of bike they owned or rode as a youth – classic motorcycling is all about nostalgia, after all. But many restorers are disappointed to find that reality doesn’t match up to rose-tinted memories, and that, in modern traffic, the bikes they remembered as nippy lightweights turn out to be underpowered death traps. That’s not the case with 197cc Villiers jobs. All right, you wouldn’t want to take one onto a motorway, or even a fast A-road, but for back road riding and VMCC runs, they’re absolutely fine. And when that ability is allied to a quality restoration and an interesting family history, you get a truly delightful bike like John Gerry’s Falcon 67. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.