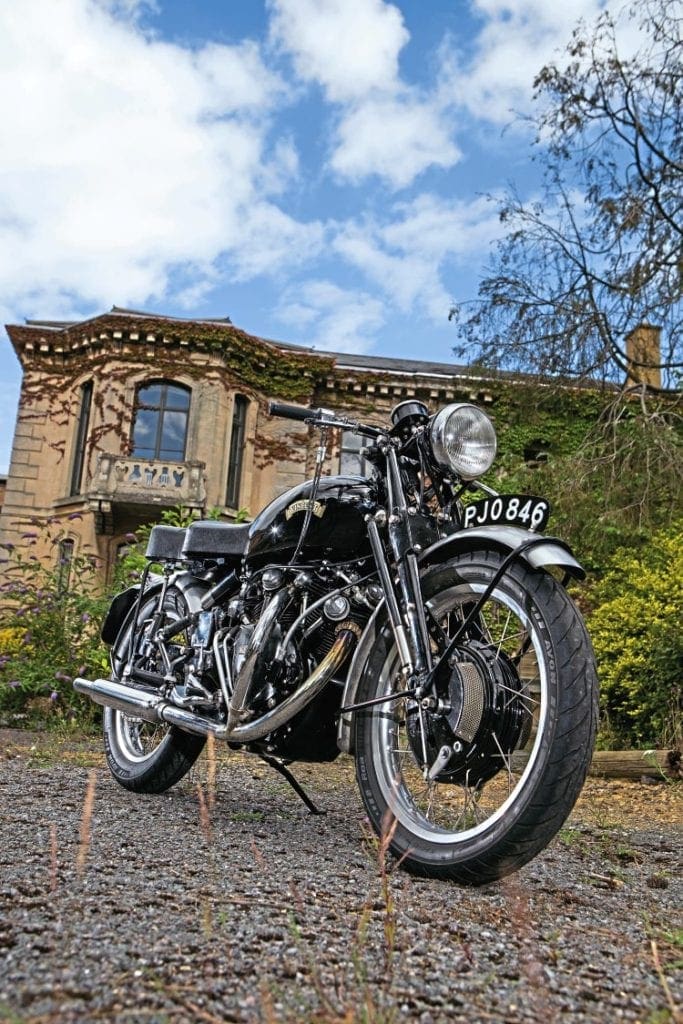

Though it was once known as ‘The Pig’, today this Vincent is anything but. In its early days it endured a hard life – and continues to be ridden with spirit.

Words: James Robinson Photography: GARY CHAPMAN

Occasionally, things can take many years to come to gestation.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

This Vincent seems to be a motorcycle that this happens to on a regular basis. For example, its build took much longer than owner Nigel Waring was planning (the build was over seven years), while Nigel and I have been talking for what seems like years about getting this feature together.

But, in both cases (Nigel’s and mine) it has been proved to be well worth the wait.

Despite all the hype, the reputation, the stories and the mythology surrounding the name, the fact is that with regards to a Vincent twin, it doesn’t disappoint, as there really is nothing like it.

As Nigel and I stood looking at his Vincent, parked up outside a disused Masonic lodge, we both mused and mulled over the whole Vincent ‘thing.’

The hows, whys and wherefores can be discussed and debated for ever and ever, but the simple and basic fact is that when the first post Second World War (so Series B) Rapide emerged onto the scene in 1946, it was a machine that boasted performance on a par with the best motorcycles being raced in the top class of world racing, while it was also the premier long-distance tourer out there too.

It was capable of being used as a commuter too, of hauling a sidecar laden with children, suitable for a spot of road racing, sprinting or hillclimbing.

A real all-rounder, but a top, high class one. Add to the mix that physically it was about the same size as said 500cc race machines and it was also a marvel of engineering free-thinking (such as using the engine as a main part of the frame, dual brakes, unit-construction) and really it is impossible to appreciate how different, how avant garde and how darned-right fabulous the Vincent was and is.

And despite the fact that the Vincent twin in its Series B, C and D incarnations (which all share an obvious, common lineage – the prewar A doesn’t so much) lasted for less than 10 years, it has remained an idol and icon of British motorcycling, still possessing an aura which no other machine matches, 60 years since the last of the 6772 (figures do vary, but that seems to be the most regularly quoted) B, C and D twins built rolled off the Stevenage work benches.

Nigel acquired his Vincent about 15 years ago, when a mate and he bought a pair of twins, with Nigel having the one in the worse condition. There was a fair amount of stuff missing, though Nigel didn’t necessarily see that as a curse. “I just thought, I’ll do what I like then.”

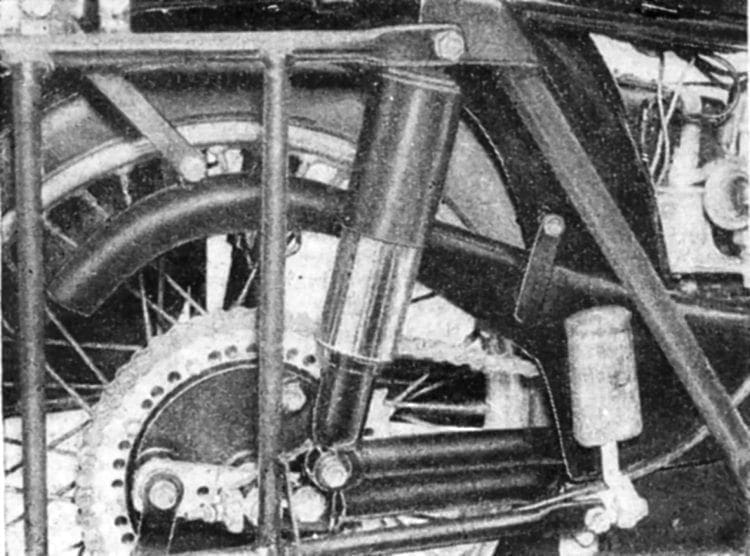

And he duly has. The Vincent has retained a relatively standard appearance, but plenty of elements have been uprated, though Nigel decided to replace the swinging-arm rear frame fitted with a B rear frame member that came with the kit.

But though the engine looks outwardly fairly standard, underneath the black-finished engines and gearbox casings, there nestles a five-speed gearbox cluster, which is a Quaife one, acquired through John Surtees.

The engine itself has been heavily breathed upon too, with Lightning (the 150mph ‘racer’ as made famous by Rollie Free on the Bonneville Salt Flats) cams, 8:1 compression ratio pistons, a Francois Grosset ignition system, then several bits from marque specialists Maughan and Sons too, including their dry clutch and crank assembly.

Nigel wishes to extend special platitudes to Maughans, as well as Frenchman Patrick Godet – both have provided many parts, much help and encouragement. Of Patrick, Nigel says: “Although things sometimes take longer than expected, Patrick’s devotion, emotion, craftmanship, knowledge and attention to detail are absolutely second to none.

He has basically rebuilt the entire bike, but in gradual phases. In fact, the bike spent so much time in France my mates said it would need to re-learn English on its return!”

There is an Alton alternator (via Godet) while the Vincent sports two ‘front’ cylinder heads, a popular performance mod in period.

Originally, Nigel was running with a pair of brass-bodied 289 Amals but after the Vincent caught fire, he decided to change to twin Mikunis… He explains: “It spat back through the carb and the next thing I knew it was on fire. It was difficult to know what to do at that point… It was covered in fire extinguisher powder but luckily the damage wasn’t too bad.”

Soon, the Vincent was retuned to fitness, but this time it was sporting Japanese carburettors, which Godet set up on his rolling road, the bike temporarily fitted with gas analysers, though Nigel still has the Amals ‘on the shelf.’

In total since it went back on the road in 2006 Nigel reckons the Vincent has done something around 3000 miles and strangely he’s never had to charge the battery (an Odyssey-made item) once, which says something for the French ignition and charging set-up, as well as the battery’s manufacturing quality.

The Vincent sports 18-inch rims front and rear, with Avon Road Rider tyres, though originally Nigel had it on standard rims, but decided to swap.

Missing components included the wheels; in fact, the front wheel that came with it had two half-width Goldie-type hubs welded together, but Nigel had something else rather special on the shelf, a Dave Degens/Dresda magnesium MV Agusta replica front brake, which was in a classic racer he used to campaign. Of the brake Nigel says: “It’s still good, but not as great as it once was.”

This Vincent is made for riding and Nigel rides it hard, being a regular attendee at various track day events, including the Beezumph at Cadwell Park and Mallory’s classic festival, among other events.

Having raced between 1996 and 2002, Nigel campaigned a host of machinery, ending up with a 500cc Dresda and some backing from proprietor Dave Degens.

But he gave up racing, as by 2002 he was campaigning two bikes and as he admits he “just couldn’t get them right.” He’s a busy man – formerly in the employ of Toyota, he is currently working as an engineering consultant with Mercedes, spending quite a lot of his time in Stuttgart – and such a career isn’t conducive to a sustained racing effort.

In fact, Nigel quit midway through the 2002 campaign, with the intention of getting the two bikes ‘sorted’ and coming back in 2003. In fact, he simply never went back to it.

Nigel has had a huge variety of machines, ranging from prewar Triumphs to modern superbikes, but now he is signed up to a simple philosophy – the Vincent shares his garage with just one other motorcycle, his collection having grown to 10 a few years ago.

But as he correctly opines, it is basically impossible to keep that many bikes in fettle as well as having a full-time job (that involves lots of time away) and maintaining a sense of balance with family life, too.

So he devotes his limited spare time to keeping his Vincent and the other garage occupant in as good a fettle as he is able to. And having ridden both his bikes, it’s a philosophy that seems to work well.

Despite the fact Nigel and I both reckoned his incredibly well-sorted and tweaked Commando (of which we will hear more at a later date) is the nicer bike to ride, the Vincent is of course giving away 25 years to the parallel twin, which needs to be kept in mind.

For some reason Vincents are rarely compared to any of their contemporaries, instead having ‘modern’ or later values imposed upon them.

But if you consider that at the time of its launch the Vincent was so unlike and ahead of everything else on offer, then the whole ‘thing’ starts to make sense.

And it is a testament to the marque’s quality that they are compared to later machines because, frankly, they are incomparable to any of their contemporaries.

What’s it like to ride?

Sat astride a Vincent feels unlike all other machines. Not only are the Stevenage-built machines ploughing their own furrow in terms of design, once aboard one could be on nothing else. T

he seat (this one came from marque specialist Bob Culver, incidentally) feels high and wide, while the trademark Vincent flat bars feel low.

Standard Vincent bars always feel narrow, though I suspect Nigel’s may be a touch wider than standard. Nigel instructs me in the starting drill – ignition on, press down the cold start (choke) lever, a few kicks with the valve lifter in, then kick while simultaneously releasing the valve lift and a little bit of throttle.

Like any motorcycle known well by its owner, Nigel makes it look easy, but it takes me a couple of attempts to find the correct throttle opening when kicking. But it starts easy enough thereafter.

Nigel’s Vincent’s throttle action is impressively light compared to other twins I’ve sampled, while the clutch is smooth and progressive too and not a bit heavy, either.

Setting off, I do my customary front brake test – this one feels pretty good, always reassuring. We head straight out into heavy town traffic and set about filtering through.

Now, this can always be a little nerve-wracking in an unfamiliar city on an unfamiliar motorcycle, but the Vincent is pleasant, docile and tractable, though its bark ensures any car driver not paying attention soon is.

Out onto the bypass and its time to give it its head. And it is brilliant. Soon, the Vincent feels familiar and solid, as we ‘drag race’ away from lights before pulling up to the next set. I can see why Nigel uses it on track. I can also see him grinning at me as he glances back. We’re having fun.

Away from the traffic light GP, we ride into the countryside.

By now, the Vincent riding position is feeling natural, while I’m relishing the five-speed gearbox too, though first gear is perhaps a touch on the tall side when pulling away, which eventually means the clutch gets a bit hot and bothered as we do several stop/starts for photographs.

Nigel has encouraged me to rev the Vincent plenty and it responds magnificently, accompanied by a thrumming boom. We get onto single track roads and our pace keeps reasonably brisk – humpback bridges, potholes and high hedges means one’s attention must be kept and though the Vincent doesn’t become overly agitated, it isn’t as settled as Nigel’s Commando, and I’m struggling, slightly in vain, to keep up with the rapid blue missile (and its rapid rider) in front.

We swap bikes for the ride back and I get to follow Nigel on the Vincent.

It’s brilliant, as we tramp round a big, open, wide roundabout, watching the Vin’s right footrests skimming the Tarmac as Nigel maintains his line, with his left hand out indicating we’re coming off the roundabout, all the while the Vincent rear wheel gently going up and down though the machine stays dead true. Impressive to behold.

And that sums this Vincent up all round.

History

Though this Vincent is a fabulous machine it its own right, it also has quite some history too, being the machine owned by legendary journalist and author Bruce Main-Smith (BMS). Bruce did epic mileages on the Vin, while it was also modified extensively – Nigel still has the rear subframe the affectionately-named ‘Pig’ (owing to its appearance, not temperament) was fitted with by BMS.

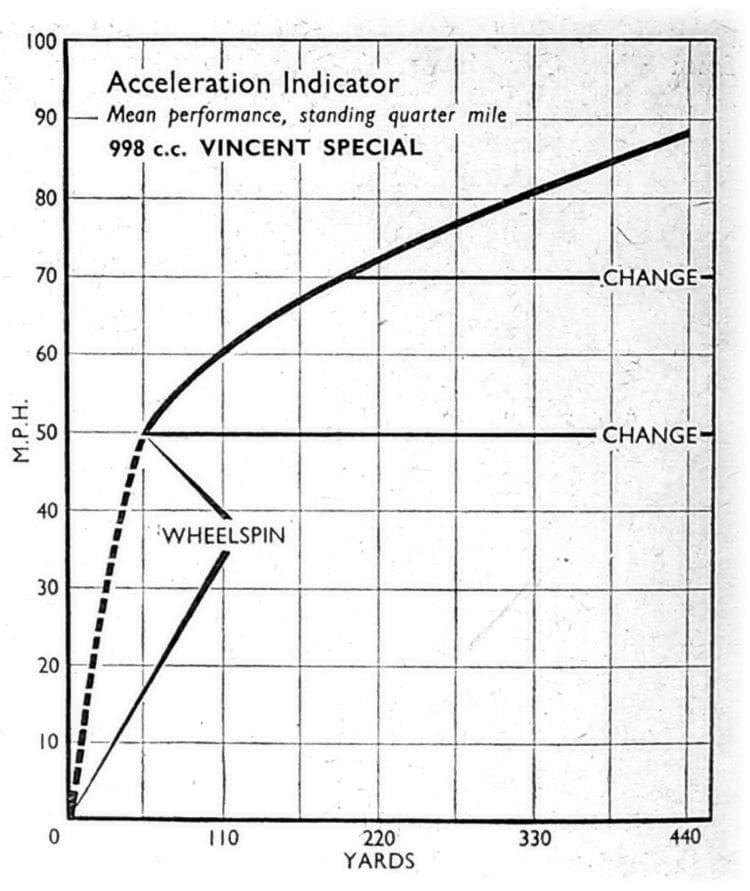

In fact, the Pig was the subject of a Motor Cycling roadtest in late 1960, which we’ve reproduced over and which makes for interesting reading. I’ll make no further comment on the performance figures quoted than to say I reckon this Vincent still has that in it. Easily.

But as for being a Pig? Not a bit of it.

Read more News and Features in the December 2019 issue of The Classic Motorcycle –on sale now!

A 998cc VINCENT SPECIAL

110mph roadster extensively modified to owner’s requirements

Motorcycling: December 29, 1960

We close the year with a Road Test that is different. It deals with a privately-owned machine of a make which (regrettably, many feel) is no longer in production. The subject is the 10-year-old “Shadowized” Vincent “Rapide” owned by staffman Bruce Main-Smith and modified by him to his personal requirements. Its history includes a spell of solo and sidecar racing. – Ed.

NOW at a mileage of 132,000, Bruce Main-Smith’s 1951 1,000cc ohv V-twin Vincent “Rapide” has been converted by the owner to meet his own priorities.

These demanded the ability to cruise indefinitely on motorways at 90 to 100mph; outstandingly good acceleration and braking to deal with weekend traffic on the A29 and A3/A283 London-South Coast routes; first-class roadholding; protection from the weather; luggage-carrying facilities and especially good lights. Further, the machine had to be as suitable for the owner’s wife on the pillion as it was for the driver.

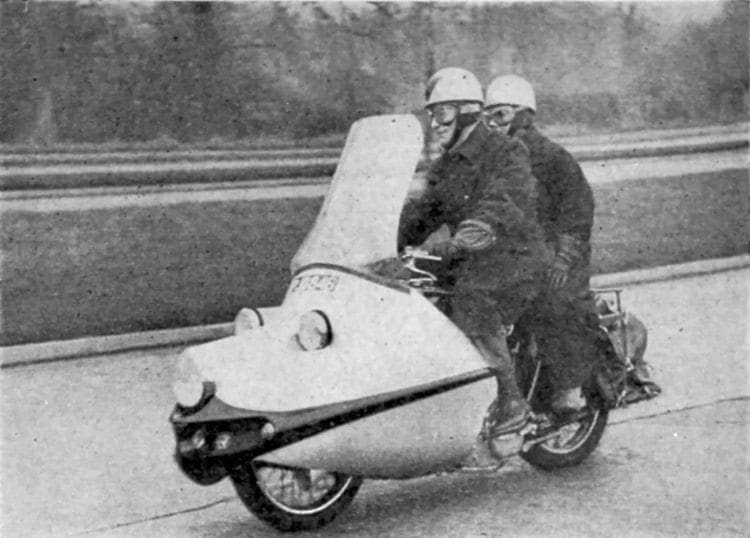

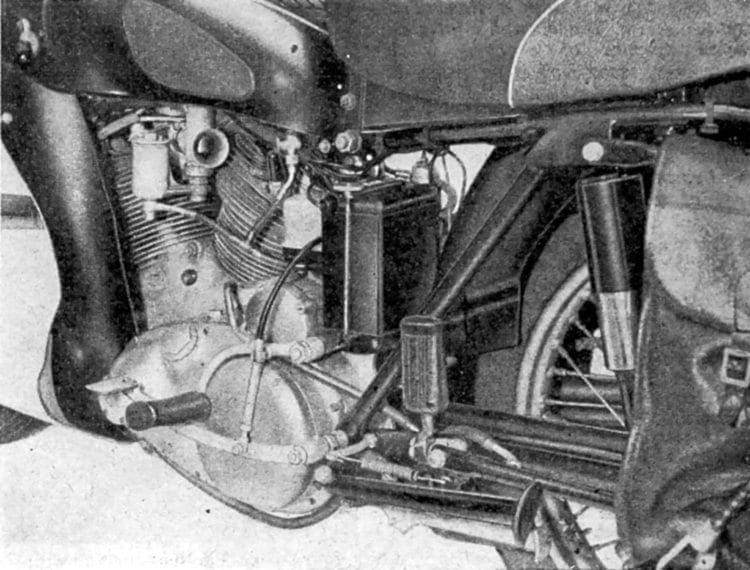

Accordingly, the following non-standard equipment has been fitted, some of it of the owner’s design and construction: “Shadowized” engine with “Picador” two-start oil-pump worm, doubling the rate of circulation; “Lightning” brakes; “conventional” swinging-fork rear suspension; an “Avon Streamliner” full-frontal fairing; qd panniers and luggage carrier and an AMC twinseat.

The immediate impression on seeing “Pig”—as the Main-Smiths call it—is of cumbersomeness. This was not dissipated when one wheeled the machine around. Steering lock was restricted, even below the limited Vincent standard, and the frontal overhang was a nuisance.

Against this, the enclosure was completely successful in keeping the rider clean and dry – even his hands and feet – and in relieving him of fatiguing wind pressure. (The Vincent “leaning on the wind” position has been eliminated by moving the footrests forward and fitting Ariel handlebars.) At speed, goggles were necessary.

The passenger received some air buffeting, though less than on a “naked” model. Really fast cruising in rain was practical. Water could not pass the front-fork gaiter. Internal leg panels tidy up the enclosure, allow the stiffening boxes to be used to carry full puncture and chain repair outfits, and direct air more onto the cylinders. Either shield could be taken off in 30 sec.

Diminished cooling by radiation made the engine run hotter than standard at low air speeds – without, apparently, any ill effects. A pleasant warmth was imparted in the wintry test period; in summer, the owner’s riding kit consists of sports jacket and flannels, with light outerwear for rain.

Once under power, the steering was faultless.

There was no heaviness at low speeds. Although the standard steering damper had been removed, the Vincent was 100% wobble-free, even when thrust hard over bumpy roads. It never nodded its head or wagged its tail.

There was undiminished ground clearance. The enclosure could not be touched down.

In the wet, sheer weight aided adhesion, the mount being both quick and extremely safe.

Roadholding was equal to that of any mount in current production.

Indeed, it was “Grand Touring” in the car sense of the term. The ride was exceptionally comfortable for this level of handling, the Girdraulic front forks making a major contribution.

Behaviour was free from pitching or any associated faults. There was no change of trim, no matter how hard the excellent brakes were applied. Application of the nominal 55 “brake horses” produced only a trace of lifting at the front; jack-knifing at the rear pivot, not unknown on standard Vincents, was completely absent.

The front forks clicked on being moved from lock to lock, indicating wear at the eccentrics. The metal-bush-pivoted rear fork was rigid laterally. The use of closed lug ends in this component, however, made rear wheel removal complicated and messy.

Steering generally was a revelation for a mount weighing 540lb, conceived in 1945 and home modified. A pillion passenger was no handicap—if anything, an asset. The front forks have Series ‘D’ trail limits, an Armstrong hydraulic unit and one Norton clutch spring supplementing each inner main spring.

The tailored riding position proved perfect for a man of much the same size and build as the owner. The tank could be both narrower, to reduce splay at the knees, and larger, to hold more than 3 gal.

The fixed footrests were just right; both their associated pedals, modified to suit, were well-placed. The pillion rests have been lengthened and cranked for the comfort of a 5-ft 1-in passenger.

With the flexibility and output of a “Shadow”– type engine, the machine had an abundance of smooth power. The crankshaft, Hartley balanced, mounts Irving-designed caged big-ends.

A continuous motorway cruise in the upper nineties revealed no vibration. But there was a protracted period, in the forties in second and fifties in third, which produced tremor rather than vibratio – an effect probably accentuated by the general smoothness. Top gear could be held down to 35mph, below which speed the extra backlash suggested a change down.

What optimum use of the gears could achieve is shown, strikingly enough, by the graph and tabulated figures; but under road conditions change-points were by no means critical.

Although third could be held to 90 or even 100mph, this was quite unnecessary. The machine has been fettled to give shattering acceleration in top gear at 45mph. Good results were forthcoming at 40; at about 43 one felt everything get into phase – then one had to hold on very tight. And pick-up persisted at 100 if the half-open throttles were suddenly fully lifted.

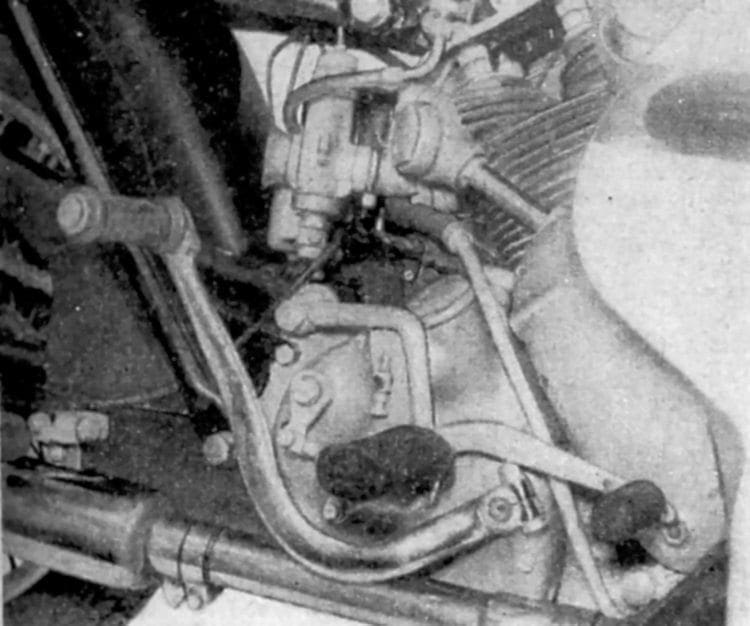

The gearbox has the low “Rapide” bottom. Top and third have been given extra backlash. Also non-standard is the multi-plate dry clutch, made from Norton parts.

This combination gave faultless gear-changes. A Vincent can be stiff to put into top around 90mph, but this did not occur. Neutral was easily found from bottom or second. The gear pedal, however, had too long a travel.

The clutch was excellent, light and jerk-free. There was no overheating, slipping or need for adjustment during the test.

Carburation was unhesitant throughout. The modified mixing chambers permitted light wrist action. General fuel consumption was 53mpg over an extended period of really hard driving. “Super” grade petrol was essential to avoid pinking.

Main jet size is 190 instead of 180 to promote reliability at prolonged high speeds. PJO 846 has not been recently decoked – in accordance with the widespread belief that this process is simply unnecessary with a “1000” Vincent.

The handbook advice of “straight” oils – SAE 50 summer, 30 winter – is normally followed. In deference to the high-speed work at MIRA, we kept to heavy oil this month and paid the penalty with an engine stiff to crank when cold.

No chokes are fitted, nor were they needed; a good flood was enough. The rear float-chamber is sensibly mounted on the left so that the petrol may be left on when the prop-stand is used; its tickler is extended for easy access.

The standard Vincent drill of raising the footrest before kickstarting was not necessary; the pedal-piece to the rebent crank is fixed permanently out; it did not foul the leg.

Vincent braking has always been superb and indeed set the road-test record for a long time. The “Lightning” racing anchors on this mount were first-class.

Pedal pressure on the single drum back stopper was less than standard for the marque. Neither it nor the Ferodo-lined dual front brake were affected by heat or rain.

The Marchal lights were admirable, especially the asymmetrical cut-off to the dipped beam of the headlamp, the set of which is adjustable from the saddle to compensate for load. The “flamethrower” spot is aimed 30yd ahead, aligned on the verge of the centre strip of the M1. The fog lamp gave a spread pattern at short range.

The note of the twin Lucas Windtone horns, set to fire up the left airscoop, was lethal at 150 yd during 90mph motorway cruising. Boosted dynamo output kept the battery up, though charging as heavy as 8 amp, was seen at times.

The power unit was oiltight with the exception of the kickstarter cover, a “dry” compartment anyway! Oil consumption however, was high at 200 miles per pint.

There was considerable engine-to-chaincase transference, which called for levelling and probably accounted for most of the oil loss. KLG FE75 plugs were used. They never fouled, even in prolonged central-work (inlet valve and rocker drainage been improved).

Exhaust silencing was up to the usual Vincent standard, which is good. Mechanically, the engine was clattery, but wear may account for some of this;. For example the cams are the originals. There was slap from the cylinder group, which has some 90,000 miles and is due for renewal.

Many detail points are worthy of comment. The special prop-stand is excellent – easily found with the foot, always supporting the machine firmly and tucking up well.

The centre-stand is really repair-maintenance equipment, so its heavy lift may be overlooked. Neither grounds on corners. Regrettably, there is no front stand, so a small jack is carried.

The handlebar mirror is free from vibration blur and was a boon. The speedometer, which had been regeared to remove optimism, was accurate. There are 16 attachment points for elastics on the luggage equipment.

To sum up. Here is a 1945-designed, 1951-built machine that has been modified for a particular purpose.

The success of those modifications in dealing with certain known Vincent shortcomings provokes, inevitably, thoughts of the mount that Stevenage might have been producing today – and points sadly to the gap left in the British production pattern by the death of the big twin.

SPECIFICATION

ENGINE

Type 50° V-twin four-stroke

Bore 84mm

Stroke 90mm

Cubic capacity 998cc

Valves Overhead (push-rod)

Compression ratio 7.3:1

Carburetters Amal 1⅛-in bore “289”

Ignition Lucas magneto with automatic control

Generator Lucas E3L 6-v 60-w dynamo with AVC and boosted output

Makers’ claimed output 55bhp/5500rpm

Lubrication Dry sump with double-output

rotating-plunger pumps

Starting Kickstarter

TRANSMISSION

In-unit gearbox with footchange

Ratios (48t. rear sprocket) 3.7, 4.4, 5.9, 9.4

Speed at 1000 rpm in top gear 21mph

Speed equivalent to revs at maximum power rating:

Second gear 73mph

Third gear 100mph

Top gear 118 mph

Primary drive Triple-row chain in oil bath

Final drive Single-row exposed chain

(both chains by Renold)

Clutch Norton multi-plate in “dry” compartment

Shock-absorber Spring-and-cam type on engine shaft

CYCLE PARTS

Frame Box-type backbone with powerunit as structural member; bolted on sub-frame.

Front suspension Girdraulic forks modified enclosed coil springs; two-way Armstrong hydraulic damper

with limit stops.

Rear suspension Swinging-fork with hydraulically-damped Armstrong units; 85-lb springs. Wheelbase 53in.

Tyres Dunlop ribbed 3.25 x 19-in front,

studded 3.50X19-in rear, both held

by security bolts and balanced .

Brakes Duo front, single rear, all 7-in dia. racing parts. Total lining area, 30 sq in

Fuel tank 3½ gallon; two taps

Oil tank Hollow upper frame member, 6 pints

Lamps Marchal: 45/36-w. adjustable head, 48-w spot, 48-w fog. Lucas: twin 6-w side. 18/6-w, stop/tail, one 3-w speedometer

Horns Twin Lucas Windtone

Battery Lucas 12ah

Speedometer Smiths modified130 mph with trip

Seating AMC q.d. two-level twinseat

Stands Centre, prop, front ink

Toolkit Too large to list; includes

full tyre and chain repair equipment

Toolbox Open compartment beneath seat

Finish Black cycle parts, power

unit in natural alloy, glass fibre enclosure in silver with

black trimmings; usual parts chromium or cadmium plated

OTHER EQUIPMENT

Modified Avon Streamliner; q.d. panniers rear carrier; Triumph tank-top luggage grid; tyre pump; special engine breather; pillion footrests; oil-temperature gauge; mirror

PRICES

Machine Listed in 1951 at £336 11s

(inc £71 11s PT)

Tax £3 15s pa (£1 7s for four months)

Makers Known in February, 1951 as

Vincent-HRD Co Ltd, Stevenage, Herts, now

Harpers Engines Ltd of same address

MOTORCYCLING TEST DATA

Conditions. Weather: Dry, cold (Barometer 29.85Hg Thermometer 36°F). Wind: N, 8-10 mph Surface (braking and acceleration): Dry asphalt. Rider: 11½ stone, 5 ft 10½ in, wearing two-piece suit, safety helmet, normally seated behind screen throughout. Fuel: “Super” grade (101 Research Method Octane Rating).

Venue: Motor Industry Research Association Station, Lindley.

Speed at end of standing 1000 yd:

East 102mph

West 94mph

Best certified MIRA, maximum

(rider upright behind screen) 109mph

Braking from 30mph (all brakes): 9½ yd

Fuel consumption:

At constant 50mph 60mpg

70mph 46mpg

500-mile overall figure 53mpg

Speedometer

30mph indicated = 30.5mph true

40mph indicated = 40.3mph true

50mph, indicated = 50.1mph true

60mph indicated = 60.4mph true

70mph indicated = 70.5mph true

80mph indicated = 80.4mph true

90mph indicated = 91.9 mph true

100mph indicated = 101.8mph true

110mph indicated = 110.8mph true

Mileage Recorder Over-reading ½%

Electrical Equipment

Top gear speed at which generator output balances:

Minimum obligatory lights 28mph

Headlamp main beam 36mph

Headlamp and either spot Not capable

Weights and Capacities

Certified kerbside weight (with oil and 1 gal fuel) 540lb

Weight distribution, rider normally seated:

Front wheel 43%

Rear wheel 57%

Tank capacity (metered):

Total 3⅛ gal

Reserve 1¾ or 6½ pints

Read more News and Features in the December 2019 issue of The Classic Motorcycle –on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.