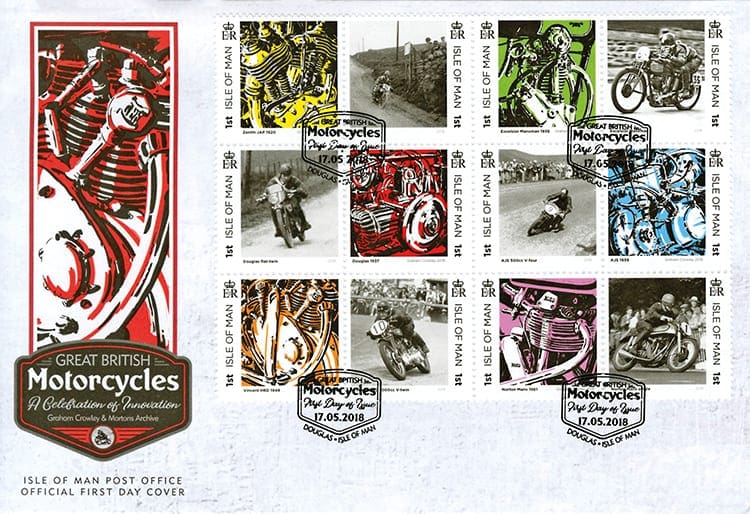

Small is beautiful. And nowhere is this more evident than the Isle of Man Post Office website. Here, alongside gushy stamp sets of Meghan and Harry’s wedding, are six philatelic examples celebrating stars of a different, less emetic kind: great British motorcycles. These exquisite graphic objects were created by graphic designer David Bloomfield and painter Graham Crowley, former professor of painting at the Royal College of Art and lifelong motorcycle enthusiast. The stamps are based on paintings Crowley made of some of the most innovative engines in motorcycle history. These machines include a Zenith, an Excelsior Manxman, a Douglas flat-twin, the water-cooled 500cc V-four AJS, a Series C Vincent V-twin and a Manx Norton.

We travel to meet Graham Crowley at his Suffolk home, where, in almost every space, there are echoes of a rare alliance between life at the epicentre of the British art world and a deep-felt passion for motorcycles – especially motorcycle engineering. Seldom are these two spheres mutually understood but in Crowley’s mind, they are one and the same. “I believe that the motorcycle engineer works in the same way as an artist,” he says. “The engineer has artistic vision, with results that are also beautiful – just like a painting or a piece of art.” To make his point, he ushers me across the courtyard of his delightful house – a conglomeration of cottages from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries – to his workshop-cum-studio.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Graham opens the large, barn-like doors of his outbuilding, behind which are boxes, workbenches, various tooling machines, a much-loved and much-used 1999 Ducati 748S and a 2004 Honda CBR600 RR. But two machines in particular stand out among the garage paraphernalia: a 1937 OK Supreme and a Series C Vincent Rapide. There’s no mistaking the Vincent-HRD. It dwarfs the OK Supreme in size and muscularity. “It’s just such a fabulous machine and so innovative. Vincent rethought just about everything, making the machine easy for people to take the bike apart at home. This was a machine designed to be worked on at home,” he said. “Look,” he says, gesturing to a finely-machined lever to adjust the chain. “Vincent thought about everything. This is a spring-loaded lever designed to ‘click’ in accordance with the chain tension. It’s incredible.”

Crowley’s machine is one of the early Vincent-HRDs, produced in 1949, just at the cusp of Vincent HRD dropping the HRD (Howard R Davies) moniker. “It’s interesting because the tank features the Vincent-HRD badge but the HRD name has been ground-off the crankcase and the blank timing cover.” Indeed, this is a machine that represents a company in flux. But while Crowley’s Series C was produced at a time of change within the Vincent company, it was no less innovative than the machines that followed. “It’s incredible,” said Crowley. “This machine has monoshock suspension and was designed to have no frame. It was so ahead of its time. And this type of engineering is symptomatic of the similarities between artist and engineer. To build a motorcycle without a frame is high thinking: if that’s not left-field, I don’t know what is. It’s visionary thinking, and comes from the same creative well as any artist. And even now, when people think of Vincents – even those outside of the motorcycle world – they consider them a piece of art.”

He said: “This idea of the motorcycle being a piece of art was celebrated in the Guggenheim Museum’s Art of the Motorcycle exhibition. That exhibition cemented the idea of motorcycles being designed pieces of art worthy of a plinth in a gallery.” It’s the same artistic engineering that Crowley admires about his OK Supreme, which has recently undergone a sensitive yet creative restoration (and updating) by engineer Gilbert Sill. “He’s also a visionary person,” says Graham. “A true artist. Look at the workmanship in the machining of the brass knobs on the tank – it’s beautiful. Gilbert reminds me of a really good watchmaker.” It’s also a lightweight, easy-to-manoeuvre machine. “It really works ergonomically,” said Crowley. “It’s got a really good seating position and I ride it as much as I can.”

But more importantly is its engine. “It’s got a JAP engine with exposed valves and the fact you could see its workings, rather than them being tucked away, was one of the reasons I bought the OK Supreme.” There’s another, more deep-rooted reason for Crowley’s interest in the exposed-valve JAP engine. And it goes all the way back to him being a young boy. “My dad had a JAP engined Morgan three-wheeler in early 1953 and I remember being fascinated by that engine. You could see all its workings and watch the valves go up and down, spitting oil and smelling all the while. It was this that undoubtedly kick-started – no pun intended – my interest in motorcycles. I loved the fact you could see the valves and the springs – these things going up and down which could propel this machine into action. It was utterly mesmerising and you didn’t get that in jelly-mould cars.”

Crowley was also fascinated by the technical drawings featured in motoring magazines as a child, according to Martin Holman’s book, Graham Crowley. This clearly contributed to his aspirations as an artist. And in 1968 he started his training as a painter at St Martin’s School of Art and then, in 1972, the Royal College of Art, from where he received an MA. But all the while, the motorcycle valves were still going – at least in Crowley’s head… Straight after finishing at the Royal College of Art Crowley started work in a small motorcycle factory, assembling high-performance bespoke machines. “I’d just finished seven years of training to be a painter and yet I was quite happy working in the factory around motorcycles. I loved it: I made turbo-charged Kawasakis, among other things. But this wasn’t a production line, it was very much a bespoke set-up.”

He returned to painting, however, with a string of highly-prestigious exhibitions and visiting lectureships and artist in residences – among them was Oxford University, the British School in Rome and the Royal College of Art. In 1998 he became the Professor of Painting at the Royal College of Art. Since finishing art school Crowley has built an international reputation as a painter with art work in public collections all over the world, from Mexico to New Zealand. And all the while, alongside his artistic career, Crowley never missed going to the Isle of Man. “I’ve been every year since 1972, whether it’s been the TT, the Manx Grand Prix or the Southern 100.”

The Isle of Man is, after all, the breeding ground and testing ground for many of the engineering innovations Crowley celebrates in his engine paintings – as featured on the stamps. And there’s one particular TT he remembers especially well – the 1978 Hailwood comeback. “I can recall watching and Hailwood brushing the hedges. You often hear the phrase ‘he was using all the road’ and he really was. Everyone drew breath as he passed.” A touching memento of Crowley’s long-standing love affair with the Isle of Man TT is upstairs in his studio. “Come on,” he says, moving in a manner like a child – not a sexagenarian. And there, lying flat on an armchair in his studio, is a hand-knitted TT cardigan. “I’ve had this since the Seventies,” he says. “It’s very much like the prewar knitted cardigans people wore,” he enthuses.

Overlooking a meandering cottage garden, the studio itself has all the hallmarks of an artist’s space. There are paintings stacked against walls, easels in action and it’s soaked in bright, natural light. But there’s one exception: his paints and brushes are ordered. Unlike most studios, this one isn’t messy with empty pigment tubes, scraps of rags and half-cleaned brushes, it’s controlled and considered. Crowley’s studio is more like an engineer’s workshop. “I approach painting in the same way as an engineer. Only I am concerned with the materiality and physical properties of the paint, an engineer is concerned with design and engineering.” In Crowley’s world – his home – his enthusiasm for motorcycles and his painting take place, appropriately, under one roof.

But it’s soon time to leave the studio. “Come on,” he says, again moving in his signature sprightly manner. “There’s one more thing to show you.”

We leave the outbuilding and enter his kitchen: an archetypal country cottage kitchen where, on a huge bench-like wooden table, lay dozens of albums of stamps. “I’ve been collecting stamps since I was a kid,” he says, wading through leaves of stamps – each one a tiny zeitgeist of social history – until he finds what he’s looking for. “Here we go,” he says. “The Isle of Man Steampacket stamps. These are from 1955 and were produced to celebrate the British Sailor’s Society.” It’s a fitting part of his collection. Beside the umpteen stamp albums is a metal box. “It’s the tin box for the sets of prints of the paintings used on the stamps,” says Graham. “I like the box because it takes me back to my days as a punk fan. It reminds me of the Public Image Ltd metal box album.” And so it’s come full circle: Crowley’s punk days, his career as a Royal Academician painter, his love of motorcycle engineering and his philately. “When I was asked about doing this project for the Isle of Man Post Office I couldn’t believe it. I’ve been a TT fan all my life, I’m a painter and I collect stamps. I really can’t think of anyone more qualified for the job.”

And on that note, looking at Crowley beaming among his stamp collection, I cannot argue.

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.