“It’s a mixture of fate and circumstance,” says Don Hunt, recalling the day in 1978 when he suddenly became the owner of a 1923 James Model 10 combination. “I used to go to auctions with my pal Dan Geary and we’d bid as high as we dared for all sorts of things, though we never won any of them. I suppose I was confident of failure when I decided to have a go for this old sidecar outfit, but when the hammer came down £100 over my self-imposed budget and I realised that I’d won it, I started wondering about things like whether it had cylinder compression, or indeed any internals at all.”

Caught on the hop by his impulse buy, Don had to drive back home to Hertfordshire from the auction at Donington Park to collect a trailer, which he jury-rigged to accommodate the outfit’s five-foot width. While his wife Margaret cast an approving eye over the sidecar’s plush upholstery, Don’s children whooped with glee when the engine started after a couple of kicks. There followed a delightful decade of outings to traction engine rallies and village fêtes, where the James three-wheeler’s antiquity and novelty value guaranteed free entry for the whole family.

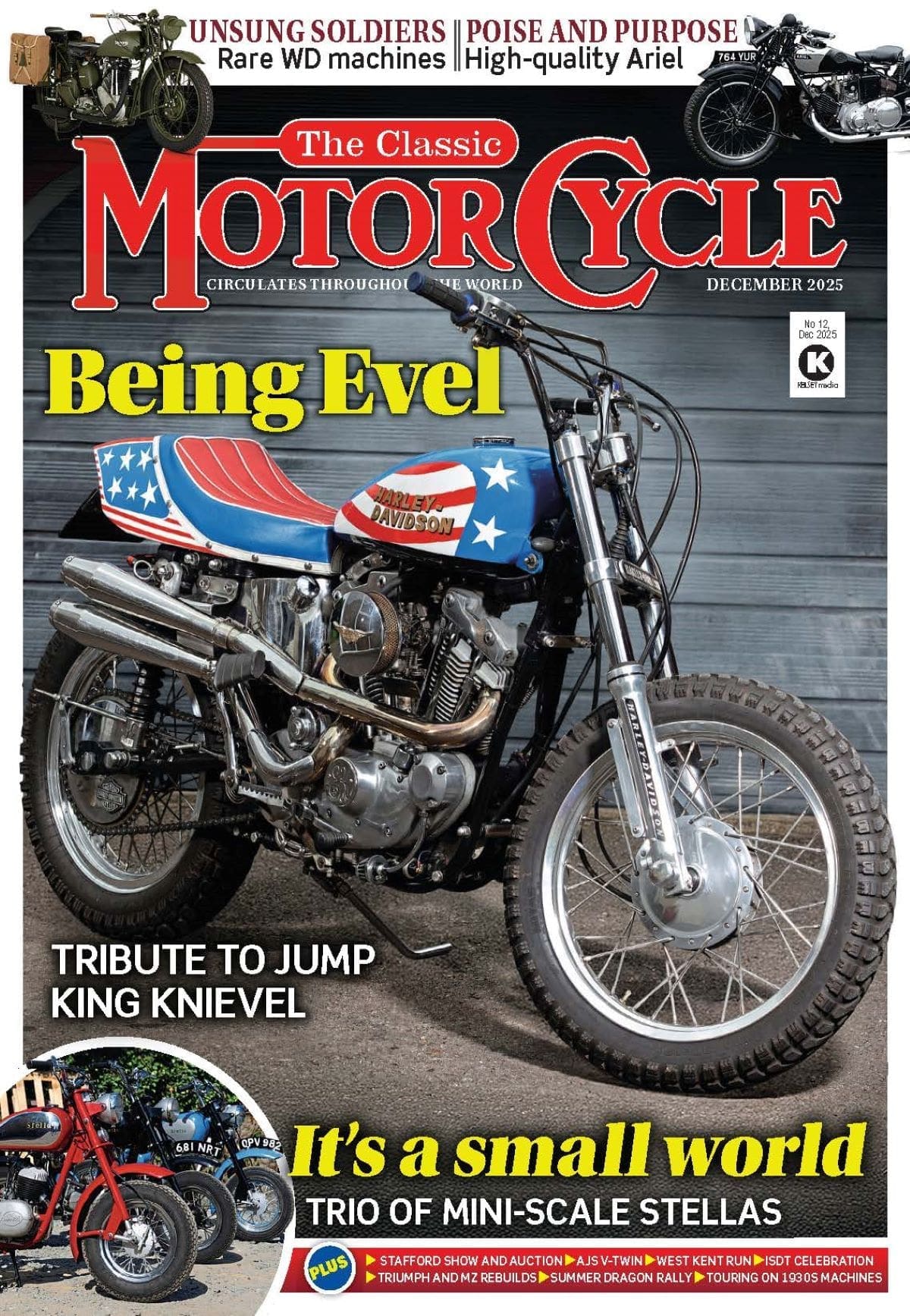

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Inevitably, time caught up with the side valve V-twin motor, which became increasingly noisy until loose flywheel rivets caused Don to stop riding it and think about its overall condition. “The engine had always started quite easily and somebody had clearly spent quite a bit of time maintaining it,” he says. “Whoever it was must have been technically adept though amateur in craftsmanship, I think.”

Inevitably, time caught up with the side valve V-twin motor, which became increasingly noisy until loose flywheel rivets caused Don to stop riding it and think about its overall condition. “The engine had always started quite easily and somebody had clearly spent quite a bit of time maintaining it,” he says. “Whoever it was must have been technically adept though amateur in craftsmanship, I think.”

In examining the machine closely and researching its specification, Don began more fully to appreciate what he had bought on a whim. “When I compared it to the catalogues and spares lists, I found that even those things that looked out of place, things I had assumed were replacements like the different types of control lever, were actually correct for this model. Some cycle parts must have been produced in very small quantities, since James liked to do things in-house, and yet, so far as I could see, the bike was original in every way apart from its paint, which was bright red.”

The originality extended to the sidecar, which seemed to be the only extant example of its type still attached to a Model 10 and thus, the James outfit made its own case for refurbishment. Don explains, “I have four descending priorities in motorcycling: one is to ride them, two is to fix them so I can keep riding them, three is to repair them when necessary and four is to renovate or rebuild them. So you can appreciate that number four would be exceptional, but in this case I made up my mind to do whatever was necessary to preserve it in running condition.”

The original, pre-WWI three-speed 495cc James ‘Twin’ was augmented by a 662cc variant in 1919, the 749cc version appearing two years later. A lighting set powered from a Lucas magdyno cost an additional £11 in 1923, when the correct sidecar for attachment to a Model 10 would have cost £35 to buy separately. It could seat an adult and child side-by-side on an upholstered seat, the coach-built sidecar body being cushioned by a pair of quarter-elliptical springs at the front and c-springs at the rear of the weldless tubular steel chassis. A quickly-detachable wheel was interchangeable with both the front and rear wheels of the motorcycle, and a spare wheel fitted in the boot. Four speeds became an option from 1929 until the entire range switched to two-strokes in 1935, the ‘famous’ James name finally disappearing with the collapse of Associated Motor Cycles in 1966.

The original, pre-WWI three-speed 495cc James ‘Twin’ was augmented by a 662cc variant in 1919, the 749cc version appearing two years later. A lighting set powered from a Lucas magdyno cost an additional £11 in 1923, when the correct sidecar for attachment to a Model 10 would have cost £35 to buy separately. It could seat an adult and child side-by-side on an upholstered seat, the coach-built sidecar body being cushioned by a pair of quarter-elliptical springs at the front and c-springs at the rear of the weldless tubular steel chassis. A quickly-detachable wheel was interchangeable with both the front and rear wheels of the motorcycle, and a spare wheel fitted in the boot. Four speeds became an option from 1929 until the entire range switched to two-strokes in 1935, the ‘famous’ James name finally disappearing with the collapse of Associated Motor Cycles in 1966.

Don worked as a consultant engineer in several industries during the latter decades of James production. He had begun his career at Fosters of Lincoln, in a traditional ‘premium’ apprenticeship that combined general education with technical skills. The firm of Fosters had designed and built the first military tanks, and like James, did almost all of its fabrication in-house, so Don became an engineering generalist, subsequently able to work on projects ranging from Concorde to Dunlop tennis balls. He calls his approach methodical, but not that of a perfectionist, and so the James restoration began with procedural documentation, as each separate task was entered on a project planning sheet. Don then went over the fine details with his friend, the late Bernard Wilkinson, who was a fellow engineer and expert machinist. Between the two of them, a specification was drawn up that distinguished between those items that could be reclaimed and those needing replacement.

When it came to actually doing the work, Don found himself hovering somewhere between enthusiasm and passion, while trying not to become obsessive. “I have learned that the time it takes me to do 95 per cent of a task is about equal to the time it takes to complete the last five per cent, and generally I’m content with 95 per cent,” he says. “Besides, I would rather see imperfections where an original component has been repaired than fit a replica.” Consequently, a large dent in the offside rounded edge of the exhaust collector box had to be cut, knocked out and re-welded by a specialist. The rider’s seat had frayed around the edges, so Don had it re-covered in leather by John the Stitch in Thame, Oxfordshire. Many of the original fasteners were nickel plated, but had rusted beyond serviceability, so Bernard found a grade of stainless steel that was similar in appearance and fabricated replacements.

When it came to actually doing the work, Don found himself hovering somewhere between enthusiasm and passion, while trying not to become obsessive. “I have learned that the time it takes me to do 95 per cent of a task is about equal to the time it takes to complete the last five per cent, and generally I’m content with 95 per cent,” he says. “Besides, I would rather see imperfections where an original component has been repaired than fit a replica.” Consequently, a large dent in the offside rounded edge of the exhaust collector box had to be cut, knocked out and re-welded by a specialist. The rider’s seat had frayed around the edges, so Don had it re-covered in leather by John the Stitch in Thame, Oxfordshire. Many of the original fasteners were nickel plated, but had rusted beyond serviceability, so Bernard found a grade of stainless steel that was similar in appearance and fabricated replacements.

The motorcycle’s frame was so badly pitted the question arose of whether it would be strong enough for continued sidecar use. It presented the greatest challenge to Don’s philosophy and he explains the science behind the testing procedure: “With most of the paint removed, Bernard and I went around judiciously hitting it with a hammer, eventually forming the conclusion that it was still solid and the alignment looked pretty good too, so off it went for enamelling.” The fuel tank was in better shape and Don persuaded an enthusiast owner of a similar James model to remove the tank of his unrestored machine, revealing unfaded paint on its lower surfaces. The VMCC's marque specialist obtained a match with the common Rover colours of Mexico Brown and Tobacco Leaf, which were set off nicely with gold and red pinstriping, applied by hand. A pair of James transfers from the VMCC finished the job.

Don had the flywheel re-riveted and stripped the all-metal clutch, which was quite serviceable, while Bernard pronounced the gearbox internals to be in ‘perfect’ condition. Being a de Luxe model, the motor had detachable cylinder heads that helped with its disassembly and its internals proved to be in good order, testament to its sound design. Engineering clearances in the top end were within tolerance and so were left alone, but the big end bearings were replaced in anticipation of further work with a full complement of passengers. Following a three-year restoration, the outfit underwent its sternest test by ascending Sunrising Hill during the VMCC’s annual Banbury Run, where it won the Feridax Trophy in 1998 and subsequently the Mortimer Shield too.

Don had the flywheel re-riveted and stripped the all-metal clutch, which was quite serviceable, while Bernard pronounced the gearbox internals to be in ‘perfect’ condition. Being a de Luxe model, the motor had detachable cylinder heads that helped with its disassembly and its internals proved to be in good order, testament to its sound design. Engineering clearances in the top end were within tolerance and so were left alone, but the big end bearings were replaced in anticipation of further work with a full complement of passengers. Following a three-year restoration, the outfit underwent its sternest test by ascending Sunrising Hill during the VMCC’s annual Banbury Run, where it won the Feridax Trophy in 1998 and subsequently the Mortimer Shield too.

On the road

The James starts easily for me, with the promise of clear roads ahead (albeit with a queue of traffic behind) on a perfect sunny day, as I prepare for a leisurely tour of the Hertfordshire countryside. The all-metal clutch, consisting of 11 alternating steel and bronze plates, has a sticky feel when cold that makes first gear selection into a noisy effort, but once warmed up it performs as well as any cork-lined unit. The clutch offers the option of either left hand or right foot operation, although not both simultaneously, as the outer cable has a tendency to become unseated when slack.

The inverted lever on the left handlebar is the valve lifter and the smallest lever retards the ignition. On the right handlebar, the top lever is the air control and the bottom is the throttle, with an inverted front brake lever on the offside. The gearchange gate is marked Low, Medium and High, and the ratios are correctly spaced for sidecar duty. Wide leverage on the handlebars gives a light feel to the steering, which is commendably precise, although left-hand corners are taken with more poise than right-hand ones. Brampton ‘Biflex’ front girder forks offer spring cushioning in both vertical and lateral planes, which alters the trail but does not upset the handling with a sidecar attached.

Don describes his riding style on the James as ‘majestic,’ which seems an appropriate mindset for riding ‘The King of Motorcycles.’ The outfit is 11 inches wider than a contemporary Austin Seven but does not have the benefit of a reverse gear, so my senses strain forwards as we negotiate narrow rural roads leading to the village of Aldbury, cruising at 40-45mph with bursts up to 50mph. Although the sidecar has no braking, the motorcycle’s brakes are up to the job of meeting oncoming traffic, since Don has increased the thickness of each outer drum from 1⁄16 to 1⁄8 inch, preventing heat distortion.

Don describes his riding style on the James as ‘majestic,’ which seems an appropriate mindset for riding ‘The King of Motorcycles.’ The outfit is 11 inches wider than a contemporary Austin Seven but does not have the benefit of a reverse gear, so my senses strain forwards as we negotiate narrow rural roads leading to the village of Aldbury, cruising at 40-45mph with bursts up to 50mph. Although the sidecar has no braking, the motorcycle’s brakes are up to the job of meeting oncoming traffic, since Don has increased the thickness of each outer drum from 1⁄16 to 1⁄8 inch, preventing heat distortion.

Picturesque Aldbury has been a frequent backdrop in films and television, including episodes of The Avengers and Inspector Morse. The 1923 James outfit brings its own period glamour to a much-filmed location outside the Greyhound pub, a duck pond and dilapidated wooden stocks beneath a spreading oak tree completing the scene. It’s little surprise that, given the affection in which it is held, the James has been in demand for the weddings of family members and friends.

In its day, the Model 10 with sidecar would have been not so much an enthusiast’s choice as luxury transport for people who prospered after WWI. Family-friendly features, such as fully-enclosed chain drive and plush upholstery, extended the outfit’s appeal to non-motorcyclists, while thoughtful engineering touches, such as a Rotherham mechanical oil pump, castellated engine mounting nuts and interchangeable wheels enhanced its reliability. To buy one new in 1923 would have cost less than a small car, although this was the same year that the new 747cc Austin Seven began to capture the market, costing less than £60 more.

In its day, the Model 10 with sidecar would have been not so much an enthusiast’s choice as luxury transport for people who prospered after WWI. Family-friendly features, such as fully-enclosed chain drive and plush upholstery, extended the outfit’s appeal to non-motorcyclists, while thoughtful engineering touches, such as a Rotherham mechanical oil pump, castellated engine mounting nuts and interchangeable wheels enhanced its reliability. To buy one new in 1923 would have cost less than a small car, although this was the same year that the new 747cc Austin Seven began to capture the market, costing less than £60 more.

Don credits the late Bernard Wilkinson and several other friends with helping to make the James’s restoration possible to the high standard you see here. Now, aged 83, he reflects on a lifetime of motorcycling and engineering activity, culminating in the custodianship of a unique piece of motoring history. “I have always felt a sense of personal responsibility to do a decent job and in this case I’m delighted with the result, which is a fun vehicle that is much-loved by the entire Hunt family,” he says. ![]()