I wonder if Edgar Lawrenson of Lancaster is still with us, or if any of his relatives read The Classic MotorCycle. If so, they’ll be fascinated to learn that the Norton he bought in October 1953 is still going strong.

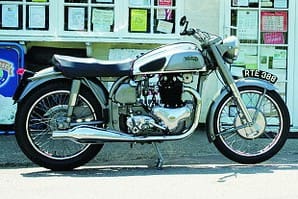

Of course, all man/machine relationships evoke some curiosity, but several factors make this Norton and its first owner especially interesting. For one thing, it’s an extremely early example of a Featherbed-framed Dominator. Many people think the two terms are synonymous, but the Dominator title had been coined for the Model 7 in 1949, when Norton’s new twin engine was fitted to the ‘Garden-Gate’ frame of the contemporary ES2. The heavy brazed-lug loop with its plunger suspension was adequate for the single, but it didn’t do the sporty twin justice, and in 1952, the Dominator gained the McCandless duplex frame that had hitherto only featured on the racers.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The new machine was named the Model 88 Dominator De Luxe to differentiate it from the previous model – which remained available until 1955 – and it was instantly apparent that here was a unique combination of looks, performance and handling.

The new machine was named the Model 88 Dominator De Luxe to differentiate it from the previous model – which remained available until 1955 – and it was instantly apparent that here was a unique combination of looks, performance and handling.

Those were the days of ‘export or die’, however, and it was mid-1953 before the Model 88 was available on the home market, where it would undoubtedly have become a market leader (perhaps the market leader) if it hadn’t been hampered by a very high price tag. That was inevitable, really, as Norton (like Velocette, Douglas and other specialist manufacturers) was never able to produce motorcycles fast enough to achieve the economies of scale that would have brought the prices down and encouraged further sales… and so on.

Things were bad enough that Norton was taken over by Associated Motor Cycles early in 1953, but even the giant AMC concern was unable, or unwilling, to provide the massive investment necessary for Norton to compete with the likes of Triumph and BSA. In fact Norton at Bracebridge Street wasn’t even given a proper assembly line, so it was not surprising that the new Dominator cost nearly 20 per cent more than the contemporary Triumph Speed Twin. Even the hottest thing on the market – Triumph’s 650cc Thunderbird – cost significantly less than the Norton, which – to further degrade its prospects – was only marketed in half-litre form until 1956.

As a result, the Dominator 88 must have been a very rare sight on British roads in 1953; but one of the things that makes this particular one even more remarkable is that before long it was seen on the war-torn roads of mainland Europe as well! Perhaps Mr Lawrenson had his epic trip in mind when he bought his new bike, as it was soon equipped with modest panniers and off he went to tour Spain.

It’s a trip that most of us would think twice about tackling today, but the confidence needed to ride a brand-new bike hundreds of miles on dodgy, often unmade, roads is breathtaking. Nowadays we’d probably carry an internet-ready laptop to call up spares, but even international telephony was uncommon and unreliable then, and any problems would have involved a lengthy postal delay, to say the least. Yet Edgar Lawrenson travelled alone, he didn’t seem to carry much baggage, or many spares, with him, and he still apparently had an extensive, trouble-free and enjoyable holiday.

It’s a trip that most of us would think twice about tackling today, but the confidence needed to ride a brand-new bike hundreds of miles on dodgy, often unmade, roads is breathtaking. Nowadays we’d probably carry an internet-ready laptop to call up spares, but even international telephony was uncommon and unreliable then, and any problems would have involved a lengthy postal delay, to say the least. Yet Edgar Lawrenson travelled alone, he didn’t seem to carry much baggage, or many spares, with him, and he still apparently had an extensive, trouble-free and enjoyable holiday.

How do I know all this? Well, some of it is surmise, I admit, but there is some evidence to back up my guesses, because another remarkable thing about this saga is that the photographs taken by Mr Lawrenson have stayed with the bike for the ensuing half-century! And they are much better than the postage-stamp sized holiday snaps you’d expect from the days of the Box Brownie. Edgar was a evidently a competent and well-equipped photographer, and there are about a dozen nicely composed six by eight inch prints showing the Norton parked up in scenic villages, or, more usually, alongside empty, dusty, roads that wind off into distant mountains.

However, the images tell you much more than the obvious fact that Mr Lawrenson and his Model 88 travelled through an attractively undeveloped country. For one thing, there is no passenger or riding companion, or even Edgar himself, in any of the shots, so you can tell that he travelled solo. Similarly, you can see that he had a modest amount of luggage, and he would surely have taken a photograph of the stricken Norton if it had ever been sidelined by a breakdown.

However, the images tell you much more than the obvious fact that Mr Lawrenson and his Model 88 travelled through an attractively undeveloped country. For one thing, there is no passenger or riding companion, or even Edgar himself, in any of the shots, so you can tell that he travelled solo. Similarly, you can see that he had a modest amount of luggage, and he would surely have taken a photograph of the stricken Norton if it had ever been sidelined by a breakdown.

Mr Lawrenson must have been pleased with the Dominator, as he kept it for another five years before passing it on to a fellow Lancastrian. The old buff logbook records a few other names – mostly in that area – but the trail then goes cold until a decade or so ago, when the Norton belonged to a chap in Staffordshire.

Readers may recognise Hampshireman Roy Houghton, whose splendid Ariel-Norton special we featured back in 2001 and whose Trident-powered Triton was in last month’s issue. Well, when Roy was developing the Squariel Special, he advertised for a suitable rear mudguard, and when this Staffordshire fellow replied, he mentioned that he also had a small collection of Nortons, which included an early Dominator with a bolt-up frame and single-sided brakes. As that model ticked a box on Roy’s personal must-have list, the inevitable result was that his ‘wanted’ advertisement involved him in a lot more expense than just buying a mudguard!

Still it got him a bike he’d always desired, and it came with the priceless provenance of those photographs. Plus – like Edgar Lawrenson – Roy has thoroughly enjoyed owning and using the Model 88 Norton. And well he might, as the early Dominator is a totally vice-free motorcycle that’s a joy to ride.

In these days when superbikes often have bigger and more powerful engines than ordinary cars, it’s hard to imagine that the Dommie 88 was ever regarded as a big sports motorcycle. After all, its top speed is nowhere near the magic ‘ton’, and its weight and size are modest by any standard.

In these days when superbikes often have bigger and more powerful engines than ordinary cars, it’s hard to imagine that the Dommie 88 was ever regarded as a big sports motorcycle. After all, its top speed is nowhere near the magic ‘ton’, and its weight and size are modest by any standard.

But just imagine yourself back in 1953 when motorcycles were mostly seen as the working man’s transport, not a fashion statement or a hobby. There were lots of pre-war machines still giving everyday service, and many commuters were busily bolting minuscule motors onto the back of their pedal cycles. In this sea of grey porridge, getting your hands on a decent ex-War Department Matchless G3LS would have been a big deal, and owning any new motorcycle – even one of the rigid framed side-valves that were still available – would have been beyond most people’s dreams. What an impact must have been created by this brand-new Norton with a race-bred frame, glamorous styling, and performance way above what could actually be used on contemporary roads. Why, even the class-leading Tiger 100 only came with either a rigid frame or the sprung hub that was already earning itself dubious press.

And while fans of other marques might disagree over which was the best looking big twin, few could fail to think that the Model 88 was the most modernistic of them all. The boxy shape of the Featherbed chassis lent itself to strong horizontal styling that some unsung genius emphasised with a uniquely flat-bottomed petrol tank and dual seat. The mudguards had an understated elegance, in contrast to the vintage-type valances still seen on some competitors, and the ‘pear drop’ silencers were similarly stylish yet individualistic, as were the cast-metal brake and clutch levers.

Some might argue that the fork-top instrument panel was less neat than having the speedometer in the headlamp, but it probably seemed ultra-modern at the time. Anyway – like the 1930s fad of mounting instruments in the petrol tank – it was soon seen to be more trouble than it was worth and the instruments were relocated at about the same time that a battery box – mirroring the shape of the oil tank – was introduced to tidy up the only ‘bitty’ part of the appearance.

Just a couple of features seen on the first Featherbed Dommies would soon be regarded as old-hat, although they were commonplace then. These were the steel single-sided brakes, and the cast-iron cylinder head, but their employment had more to do with Norton’s shortage of in-house resources than with lack of ambition, and they switched to more avant-garde aluminium castings as soon as they could.

Just a couple of features seen on the first Featherbed Dommies would soon be regarded as old-hat, although they were commonplace then. These were the steel single-sided brakes, and the cast-iron cylinder head, but their employment had more to do with Norton’s shortage of in-house resources than with lack of ambition, and they switched to more avant-garde aluminium castings as soon as they could.

Similarly, Norton never made its own Featherbed frames – that part of the job was always contracted out to tubing experts Reynolds. That was great for quality, but a death knell for profits, and having to buy in so many motorcycles components must have made a significant contribution to Norton’s continuing inability to challenge the mighty BSA and Triumph in the mass-production stakes.

And that was a great shame because it’s made Dominators comparatively rare today, and while any Model 88 is a lovely machine to ride, the early ones have a charm and civility all of their own. The iron head may have restricted the absolute power output, but that was already limited by the poor petrol currently available, and the more substantial head certainly cuts down the chatter from the valve-gear.

Interestingly, among the documents that came with his Dominator, Roy Houghton found a receipt from Norton specialists Taylor-Matterson for a pair of high compression pistons – fitted in later days when 100-octane petrol was freely available. But what goes around, comes around, and lower-octane fuel is now the norm, so one of the few changes Roy has made is to refit low compression pistons. The Model 88 has now regained its natural easy starting and unthreatening performance, and the bottom end has an easier time as well.

In describing the performance as unthreatening, I’m not implying that the Model 88 is gutless; far from it, it will accelerate as fast as a modern saloon car, and it is quite capable of maintaining motorway speeds. What I mean is that take off is free of snatch, there are no significant vibration periods and no flat spots in the acceleration. No nasty surprises at all, in fact.

And then, of course, there’s the Featherbed frame. If you’ve never ridden a McCandless-framed Norton, perhaps I should point out that its nickname is a bit misleading as the suspension is stiffish, and nowhere near armchair – let alone featherbed – standard. But that doesn’t mean that you’ll be uncomfortable, as the wide and well-padded dual seat provides ample support for your backside and thighs, and the footrests and handlebars are well-placed.

And then, of course, there’s the Featherbed frame. If you’ve never ridden a McCandless-framed Norton, perhaps I should point out that its nickname is a bit misleading as the suspension is stiffish, and nowhere near armchair – let alone featherbed – standard. But that doesn’t mean that you’ll be uncomfortable, as the wide and well-padded dual seat provides ample support for your backside and thighs, and the footrests and handlebars are well-placed.

Incidentally the fabled ‘Norton Straights’ that owners frequently fitted to Dominators in the 1950s (before they became a factory option) were originally intended for Vincents. They provided a racier look and feel, but, to be honest, the higher handlebars are a much better choice for any touring Norton.

The bars are a mere detail though; the frame’s the thing. And, as it ultimately proved quite capable of taming the 750cc Atlas with nearly twice the horsepower, it’s never going to get in a tangle with the iron-head 500cc motor. The brakes, too, are perfectly adequate despite their lack of pretension, and you can use all of the performance and handling without qualms. So, while the straight-line performance may only register as average in absolute terms, things are enhanced out of recognition by cycle parts that take the stress out of maintaining high speeds.

Overall, the early Norton Dominator – or at least a really good example like this – gives off an unmistakeable aura of competence and quality that I can best describe by saying that if Marston Sunbeams had still been in business, this is the sort of machine they’d have been happy to put their name to.

Overall, the early Norton Dominator – or at least a really good example like this – gives off an unmistakeable aura of competence and quality that I can best describe by saying that if Marston Sunbeams had still been in business, this is the sort of machine they’d have been happy to put their name to.

It would be nice to know a bit more about this particular example, though. Owner Roy Houghton, for example, feels that – apart from obvious replacements like the exhaust system and some new forks parts – it’s unrestored. On the other hand, I have a sneaking feeling that it may be an older restoration, as there seems just a tad too much chromium plating, and I can’t see how the paintwork could have retained such a sheen through half a century of life, and over 50,000 miles, starting with that epic holiday under the Spanish sun.

No matter, all the right parts are there, and the machine as a whole presses all the right buttons. If I were planning an epic touring holiday in the early 1950s – like original owner Edgar Lawrenson – I’d be very hard pressed to think of a smarter or more competent machine on which to set off. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.