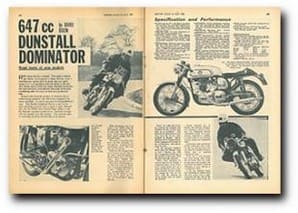

How about this for a dream? Two-miles-a-minute top whack; out-accelerate a Manx Norton; cover a standing-start quarter-mile in sprint time yet easily restart on a 1 in 4 gradient; tick-tock idling at 500 rpm. This dream travels under the name, Dunstall Dominator. On road and track it provided me with some of the most scintillating miles I've ever covered on a production bike.

Draped with Dunstall goodies, it attracted almost embarrassing attention, not only from youngsters but mums and dads. It even lit up many an old grandfather's eyes. This lavishly bedecked Norton is one of the most arresting creations ever to grace a road. Dunstall does for the 650SS what Francis Beart achieves with his Nortons—creates a work of art. Dunstall, though, sells the goodies over the counter. The customer gets to work and can thus trim the bike as he pleases.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Most economical way is to order a new 650SS with the full Dunstall treatment. Then it costs only £35 above list price. If you want even more urge, invest another £30 on internal mods. The model I used had been given the full treatment, inside and out. A glance at the specification panel will give you the full picture.

Believing that dropped bars and rearward rests are best for the track, I took the beauty to Brands Hatch for a few laps, where Dave Degens had already tried to wear it out.

With KLG FE220 plugs in, the bike was ready for racing. And a shattering performance it gave. Taking the revs to the recommended limit of 6,800 in the gears, I soon found that I easily had the legs of five-hundred. Manx Nortons.

Power was right there from the moment the twistgrip was tweaked—brutal, searing urge right up to maximum. And that sort of performance is just what pays off on the short straights of Brands. Before shutting off for Paddock Bend, I had a glimpse of 110 mph on the speedometer, with plenty more to come.

Power was right there from the moment the twistgrip was tweaked—brutal, searing urge right up to maximum. And that sort of performance is just what pays off on the short straights of Brands. Before shutting off for Paddock Bend, I had a glimpse of 110 mph on the speedometer, with plenty more to come.

To the notorious Paddock Bend itself, the Dommy clung as only a Norton can, with just a suggestion of tail wag at the bottom of the drop—even the best bred tails wag here.

Then, when clamping the anchors hard on for Druids, I recognized what a wise investment racing linings are on a super-sporting lot such as this. Contemporary Norton brakes are among the best on the road; with the addition of racing linings they are easily the greatest.

Diving downhill out of Druids into Bottom Straight, and around the ripples of Kidney, the Dominator proved remarkably steady for a production machine—a tribute, I would think, to the matched Girling racing rear-suspension units.

A pity that many production racing enthusiasts don't realize that an unsteady front end can often be cured by fitting a decent pair of matched suspension units…

Tyres are a very personal fad with racing men—some get on better with one make or type than with another, and the choice can make a world of difference to your reaction to a production racer.

GP rear covers

I, for one, applaud Avons for continuing to market their GP rear covers with a high-hysteresis mix like that of the racing covers which went out of production about 18 months ago. Identical in appearance with the old racing tyre, the GP fitted to the Dominator felt just as good as the pukka job. On the front was a standard ribbed Speedmaster Mark II.

The Dommy could be laid over until the right footrest and gear pedal caressed the road—and the rest is nearly 3in higher than standard!

(Before I rescued the bike from him, Degens had worn down to the side ribs of the front tyre and put flats on the bottom loops of the exhaust pipes. Later, Dunstall replaced these pipes with new ones guaranteed not to touch down until after the rider did!)

How did lap times compare with those of a pukka racer? Battler Degens, a Brands scratcher in the best tradition, was wearing out the Dommy at the rate of about 61.6s a lap, compared with approximately 59.6s on the six-fifty Domiracer.

No scratcher, Dixon was taking about 1.4s more than Degens on the Dominator.

Degens and Rex Butcher—another Brands ace—were both so tickled by the performance that Dunstall had to work hard to restrain them from entering his toy in the 1,000 cc races at Brands!

So much for track testing. Now for road work.

Perhaps I should put the record straight right now by repeating that I dislike dropped bars on the road because, apart from giving the impression that one is aping the racers, the low riding position transfers too much weight to the wrists during traffic riding and may give one a crick in the neck.

Moreover, as I found on the Dominator, steering lock is restricted enough to make manoeuvring in confined spaces a headache. (This is shortly to be rectified by more cutaway on Dunstall's petrol tanks, so that the hands are not trapped on full lock.)

Moreover, as I found on the Dominator, steering lock is restricted enough to make manoeuvring in confined spaces a headache. (This is shortly to be rectified by more cutaway on Dunstall's petrol tanks, so that the hands are not trapped on full lock.)

Let's be fair, though. The Dunstall riding position is tops when you are nipping along on a wide throttle opening—at over 90 mph.

As I imply, speeds nudging the three-figure mark are small beer-105 mph is a touring gait. Tweak the grip and 110 comes up on the speedometer which, incidentally, proved no more than 2 mph fast up to 115 mph; then it was slow by 5 mph!

What price do you pay in return for such spine-tingling performance? Certainly not hand-tingling vibration, for the Dominator engine had obviously been carefully built and was one of the smoothest Nortons I've ridden.

The megaphone-style silencers modelled on the old Gold Star BSA pattern—gave a sporty rasp when the engine was spinning smartly. No harm for motorway use but you required a disciplined right hand in built-up areas.

A handful of grip hard at low engine speeds—say below 4,000 rpm—provoked the tinkle of pinking, although 100-octane fuel was used. Obviously the 10.5-to-1 special pistons are right on the safe limit for road use.

Starting required a hefty swing on the crank and I found this easiest to do with the bike on the centre stud. Provided only that the air lever was closed, first-kick cold starts were usual.

Few engines of such performance will tick-over at 500 rpm or provide a waffling 2,000 rpm for traffic work, but the Dommy was docile enough for this.

And, with standard gearing, it would restart on the 1-in-4 test hill at the MIRA proving ground. Only moderate clutch coaxing was necessary for a protest-free pull-away. On the 1-in-3 gradient, only slightly more clutch slipping was called for to avoid too much pinking.

Standard 650SS

How does the Dunstall Dominator compare with a standard 650SS? Back in February, 1962, colleague Vic Willoughby – who is two stones lighter than I am and considerably shorter – obtained a mean 111 mph, and a best of 118 mph with a strong three-quarter wind. He recorded a standing quarter-mile in 14 seconds and terminal speed of 95 mph.

My acceleration was hampered slightly by a damp track, provoking wheelspin. Because the engine was over-buzzing, top gear was upped to 4.32 to 1 for mean maximum and fastest one-way speeds.

Two shortcomings common to Nortons applied to the Dunstall job. The test bike was fitted with the 1964 pattern 5/8 x 1/4in rear chain. It stretched with lightning rapidity during wet-weather riding. Latest models have the 5/8 x 3/8in chain.

In spite of being reinforced, the oil-tank top-mounting bracket fractured. And the right-hand exhaust pipe flange also fractured, allowing the pipe to come loose; these flanges have now been strengthened.

These points apart, the Dunstall Dominator is one of the most scintillating mounts to have come my way. It looks just what it is—a thoroughbred sporting lot with a remarkable all-round performance. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.